The Memoirs of Father Samuel Mazzuchelli

Posted in Father Samuel Mazzuchelli

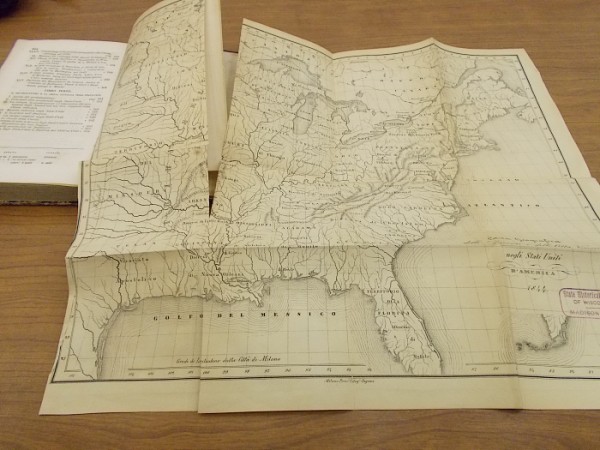

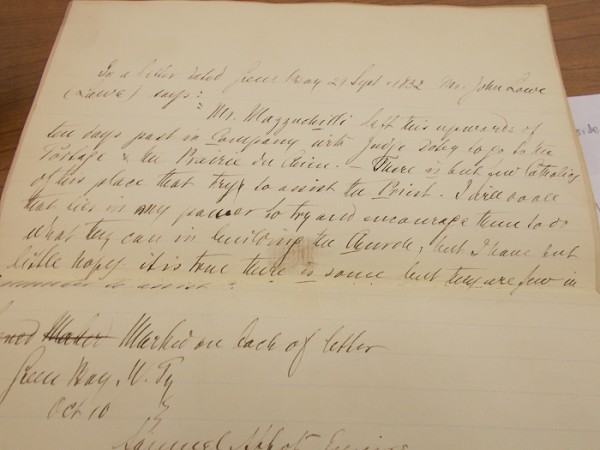

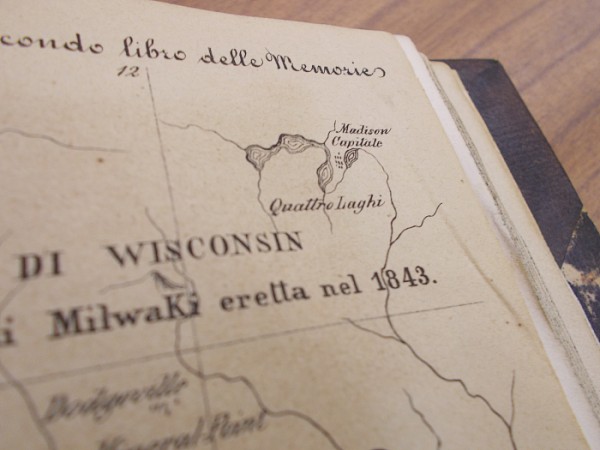

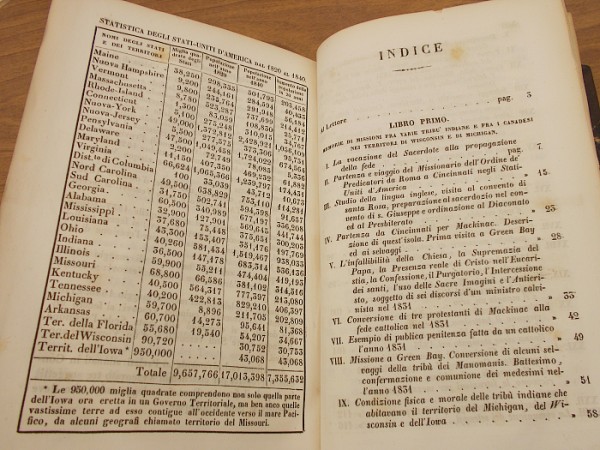

Father Samuel Mazzuchelli’s memoirs were written in 1843-44 during a visit home to Italy to recruit missionaries and raise funds to purchase Sinsinawa Mound, where he intended to found a seminary. He passed away in 1864, thus, his book dates from only the middle of his missionary activity, and prior to founding the Dominican Sisters. “Memorie Istoriche ed Edificanti d’un Missionario Apostolico” was published in Milan in 1844, its author anonymous and writing modestly in the third person. There is a very rare copy of this book in the archives of the Wisconsin Historical Society, which is the source of some images below. I have a copy of the 1915 edition translated by Sinsinawa Dominican Sister Mary Benedicta Kennedy, the source of the text below.

Father Mazzuchelli’s Memoirs are are full of detail and little stories of frontier life. His Native American converts present moving and edifying examples of Catholic practice and fidelity–especially moving when you remember that recent and brutal Indian wars were fresh in the frontier memory and Father Mazzuchelli had heard from eyewitnesses. Referred to by Mazzuchelli in contemporary popular terminology as “selvaggi,” meaning woods men, wild men, or savages, or as “children of nature,” they did not receive the best treatment by white settlers and the government, and Father Mazzuchelli, who had a great sense of social justice, tried to advocate on their behalf.

The book witnesses to Catholic doctrine and moral truth in an exceptionally lively and attractive way. Mazzuchelli, who refers to himself as “the Missionary,” encountered protestant missionaries who preached aggressively against the Catholic Faith, and Father Samuel did not hesitate to preach the truth of the Catholic Faith both courageously and with good humor that made him well approved and warmly remembered by the protestants who came into contact with him, including some of the leading members of society such as his close friend, Judge and later Governor James Doty. He speaks strongly on the false doctrines and widespread religious indifferentism he saw in America and expresses worries for the future which still strike the reader as all too clear-eyed, and startlingly we see how the frontier religious milieu led to where we are today. Father Mazzuchelli loved America and was a strong booster of America’s civil freedom of religion, as presenting great opportunity to the Catholic evangelist.

Father Mazzuchelli was also very conscious of, and makes reference to, the historical interest that his account would have in the future, since it deals with the first advent of Christianity and first celebration of Holy Mass in some places, and the founding of parishes, dioceses, cities and states–civilization formed out of wilderness. There’s no question that he was not thinking only of the popular Italian audience that his book would first meet, but had us, the readers of today, in mind and at heart. Part of the fascination of this book is that he was very successful in writing a book for people of today, especially in these same locales, about where we came from, who we are, and who we are meant to be in light of God’s love. The other part of the fascination is the modest author himself, an appealing, sensitive and warm personality, a man of extraordinary boldness, zeal, energy and accomplishments, a man of mercy, of truth and of virtue, a man who offered Christ to others in his own day, and still lovingly offers Christ to us today.

On July 6, 1993, Pope John Paul II promulgated a decree of the heroic virtue of Father Samuel Charles Mazzuchelli, O.P.. His cause for Beatification and Canonization continues, and its advancement requires the verification, according to strict criteria, of miraculous, complete and spontaneous medical cures obtained through his intercession before the face of God. Father Mazzuchelli, pray for us.

MEMOIRS

HISTORICAL

AND EDIFYING

OF A

MISSIONARY APOSTOLIC

Of the Order of Saint Dominic Among Various Indian Tribes and Among the Catholics and Protestants in the United States of America

(This translation by Sister Mary Benedicta Kennedy, O.S.D.

with Introduction by Bishop John Ireland, was first printed by

W.F. Hall Printing Company, Chicago, 1915, and copyrighted by:)

SAINT CLARA COLLEGE

Sinsinawa, Wisconsin

1915

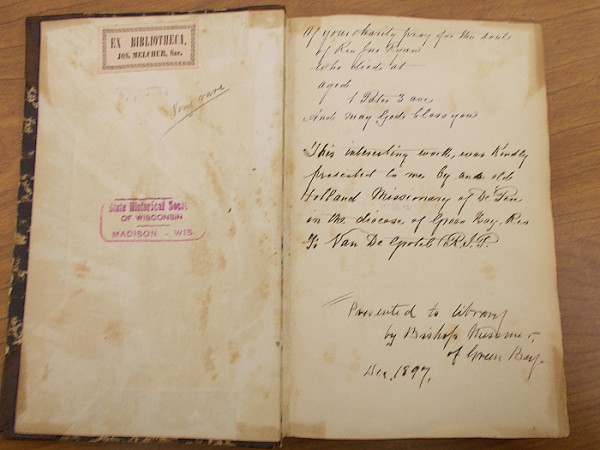

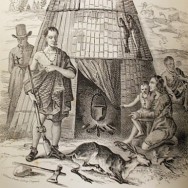

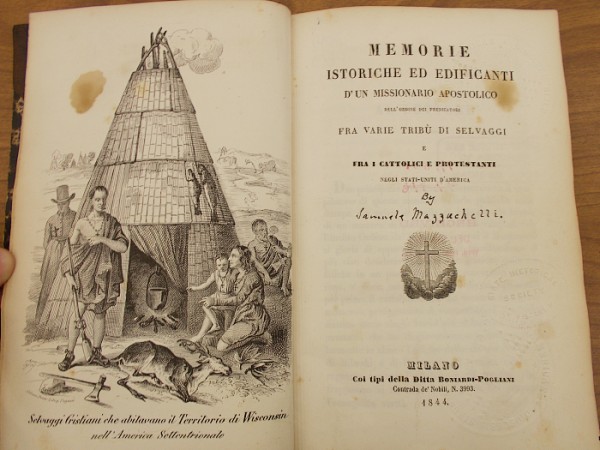

Title page spread of the original 1844 edition of the Memoirs of Father Samuel Mazzuchelli. The engraving of “Selvaggi Cristiani”, Christian Indians, is thought to be based on a sketch by Fr Mazzuchelli. Out of modesty, his name appears nowhere in the original published book, though it has been added in ink to this copy, in what strongly appears to be the author’s own handwriting, entirely plausible since this book almost undoubtedly was carried back from Italy to Wisconsin by him personally. Notes on the front flyleaf indicate that it came into the hands of “an old Holland missionary” who presented it to Bishop Messmer of Green Bay, who then gave it to the Wisconsin Historical Society in 1897.

INTRODUCTION

By the Most Reverend John Ireland

Archbishop of St. Paul

Whenever the pen of the historian traces in merited colorings the work of the Catholic Church, during the middle decades of the nineteenth century, in Michigan and in Wisconsin, in Illinois and in Iowa, a picture surely is there of singular beauty of characterization, of singular power of inspiration–that which delineates the personality and the achievements of Samuel Charles Mazzuchelli.

Great priests, great missionaries were at work in laying the foundations of the marvelous structure that today is the Catholic Church in the North Middle States of the American Union. We recall the names of saints and heroes—Baraga of Marquette; Henni and Kundig of Milwaukee; Loras and Pelamourgues of Dubuque; Cretin, Galtier and Ravoux of St. Paul. The list, however, were not complete, did not the reading repeat the name of Mazzuchelli. Mazzuchelli was the peer of the best and the most memorable—the peer in virtues that compose the great priest, in deeds that brighten the passage of the great missionary.

More yet—Mazzuchelli is unique among the men whom we account as our Fathers in the faith—unique in this, that among them he was first on the ground, first to turn the ploughshare. Others came later to take up the work he had begun, to direct and foster the growth of what he had planted. At his entrance into his labors Mazzuchelli was the solitary priest, from the waters of Lakes Huron and Michigan to those of the Mississippi River, across the wide-spreading prairies and forests of Wisconsin and of Iowa. Baraga arrived at Arbre Croche, on the northeastern coast of Lake Michigan, more than a year after Mazzuchelli had said his first mass on the Island of Mackinac. Mazzuchelli had plied his canoe on the upper Mississippi River several years before Loras was at Dubuque, or Galtier in St. Paul. Others followed in his footsteps: he had been the pathfinder in the wilderness.

Priests, indeed, had passed over the lands later crossed and recrossed by Mazzuchelli—but only in a manner that was transient and desultory. Jesuit Fathers had been there, the valorous teachers of the Ottawa, the Menominee and the Chippewa: but their missions had ceased towards the middle of the eighteenth century. Since that time priests were seen now and then around Mackinac and Sault Ste. Marie, around Galena and Prairie du Chien; but to the labors of none was there given continuity of succession. The first to do the work that was to have permanency was Samuel Charles Mazzuchelli.

Unique, too, he is under another aspect—the picturesqueness, the radiance of romance and poetry, encircling his whole story, from Milan in Italy, where he was born, to Benton, in Wisconsin, where he died.

A portrait of him survives—the only one. It is that of the Dominican novice in the Convent of Santa Sabina, in Rome, about the time when he was first dreaming of becoming the missionary in America. The high-born refinement—the “signorilità,” as his own Italy would say–shining through it, the brightness of mind, the placid resoluteness of will, foretell the later Mazzuchelli, as seen and known, while hieing whither duty called, from wigwam of Indian to hut of early pioneer, from sacristy and altar to rostrum of lecture-room or hall of legislature, from converse with the lowly and the untaught to discourse with the highest and the most scholarly—always the noble-featured, the noble-minded, the picturesque Mazzuchelli—picturesque from innate grandeur and talent, picturesque from strangeness and variety in the situations through which one duty after another happened to fling his presence. There is another transcript of the personality and the labors of Mazzuchelli—this the more complete and the more light-giving—his “Memoirs,” intended to be a simple narrative of work, year by year, during the early half of his missionary career. None will read the book without seeing in the personality and in the labors, themes, such, in dramatic power of inspiration, as pen of poet or brush of painter must love to have discovered.

Born in Milan, Italy, in the year 1806, of a family enjoying notable social distinction, Samuel Charles Mazzuchelli was, in the year 1822, a novice of the Order of St. Dominic, in Rome. There, one day, in the year 1828, while yet a sub-deacon, he listened to the first bishop of Cincinnati, Right Reverend Edward Fenwick, himself a Dominican, depicting the work to be done for God and for souls in the far-away regions of Western America. The levite was prompt in response; and soon afterwards, under the authorization of his religious superiors, he was on the banks of the Ohio River. In the year 1830 he was ordained to the priesthood; and, a few weeks later, he was setting foot on the Island of Mackinac, the most remote spot of the Diocese of Cincinnati from which tidings had been borne to the ear of the bishop.

Mackinac was picturesque in scenery and in story. The poet was at home on the pine-clad hills, laved by the waters of two great seas, Huron and Michigan. The lover of tales of romance found much to charm fancy. There the hero, James Marquette, had repeated to the wild Ottawa the mysteries of the Redemption: there a wonderful register of baptisms and of marriages told of the long-intervaled visits of the ordained ministers of Christ, and, also, of the pious sacramental intervention of the unordained, when none of the former were passing by: there, too, were the memories of fierce war between savagery and civilization, between soldier of France and soldier of England, between soldier of England and soldier of America.

To the youthful priest, however, how uninviting, how perilous the field entrusted to his zeal! Without experience, the sacred oils yet undried on his hands, he stood alone; the nearest fellow-priest two hundred miles away; around him a motley crowd of Indians, half-breeds, hunters and traders, Catholics by tradition, but, as a consequence of long privation of pastoral care, ignorant of the teachings of their faith, despairingly lost to the practices of its precepts. As a further obstacle to the work of the apostolate there was on the island a very citadel of proselytism, a school opulently endowed under the guardianship of the General Missionary Board of American Presbyterianism.

Unaffrighted, trusting firmly in the Almighty God, Mazzuchelli was quickly at work. The small chapel there before his coming—the sole home of worship in the vast parish of Mackinac, extending from Lake Huron to the Mississippi River—was put into becoming shape; and a presbytery such as scanty gifts from the faithful allowed was constructed. He preached incessantly, in French and in English: he addressed his Indian flock through interpreters: he warred against proselytizers by public conferences to which replies were challenged. The spiritual and moral transformation among Catholics was profound: proselytism was silenced: conversions from paganism and heresy were not infrequent. Nor was Mackinac the sole scene of Mazzuchelli’s labors. He sought for souls, northwards at Pointe St. Ignace, where Marquette was slumbering in an unknown grave, and at Sault Ste. Marie; westward at Green Bay, in the scattered camps of Menominees and of Winnebagoes, and at Prairie du Chien on the Mississippi River. The journeyings usually were in birch-bark canoe in summer, on snowshoes in winter—always amid severe hardships when not under imminent peril of life. At Green Bay he built a church of no insignificant proportions and opened the door of a Catholic school—at the time the only Catholic church, the only Catholic school, in the whole Territory of Wisconsin. During one of his visits to Green Bay he had the consolation of having a large class of children and adults receive the Sacrament of Confirmation from the hands of the indefatigable Bishop Fenwick. At the request of the bishop, special attention was given to the Winnebagoes. A catechism in their language was prepared through the aid of interpreters, and printed, at the end of a long and wearisome journey, in Detroit.

Meanwhile, other priests were coming into northern Michigan. Father Baraga was with the Ottawas at Arbre Croche in 1831, and in 1833 another pastor was appointed to Mackinac. The field of Father Mazzuchelli now was restricted to the Territory of Wisconsin, through the whole of which there was no other to share in his ministry.

During the year 1834 and a part of 1835 Mazzuchelli was in Green Bay, from there visiting Menominees and Winnebagoes, once going to Prairie du Chien. In 1835 he was among the workers in the lead mines in southwestern Wisconsin and northwestern Illinois. Galena now became his chief place of residence. He was serving under three ecclesiastical jurisdictions, that of Vincennes for Illinois, that of Detroit for Wisconsin, that of St. Louis for Iowa. Indians, half-breeds and traders around Prairie du Chien, elsewhere miners and pioneer land-seekers, were the elements constituting the widely-scattered flock. New experiences, new conditions confronted him: he was equal to all requirements.

It was an era of notable significance to the welfare of the Church. Vast tracts of lands were purchased by the government of the United States from different Indian tribes, and declared open to settlement. Immigrants were rushing westward by the tens of thousands: the wilderness, as by magic, was transforming itself into farms, villages and cities. Catholics were numerous: their spiritual interests were to be cared for: the foundations of the future of religion were to be laid deep and solid. To this huge task one priest, sole and solitary, was giving contribution—Father Mazzuchelli. From the year 1835 to the year 1839 none other was near to lend countenance or help.

Up and down the Mississippi went his tireless peregrinations, and far back from the river, eastward and westward, wherever cottages of settlers arose above ground, wherever the chain of the surveyor lent streets and squares to nascent town-sites. Churches were built in Galena, Dubuque, Davenport, Potosi; preparations were made for churches in Prairie du Chien and various smaller places where settlers were likely to congregate. Meanwhile, it was an uninterrupted racing, summer and winter, to points hundreds of miles apart, that sacraments be administered, that the word of God be heard by Catholics and non-Catholics. It was the mass and the sermon in the shelter of the grove, beneath humble cabin roof, in schoolhouse or village hall: it was the dogmatic conference that Catholics be strengthened in their faith, that non-Catholics, if not brought within the fold, lose their prejudices and learn to esteem their Catholic fellow-citizens: now one thing, now another—always incessant, tireless work. The only respite, his only absence from the field, was one journey over snow and ice to his old-time flock of Winnebagoes and Menominees, and a visit each year to St. Louis for the spiritual comforting of his own soul.

At last his priestly loneliness was broken: his work as precursor and pathfinder was closed. On the twenty-first day of April, 1839, the newly-appointed bishop, Mathias Loras, was in Dubuque, taking possession of his see, making the Church of St. Raphael, built by Father Mazzuchelli, a cathedral—Father Mazzuchelli, as it was his right, preaching the sermon of the occasion. Bishop Loras had with him two priests, Joseph Cretin and Anthony Pelamourgues; others soon were to be added to the number. It was a new era in the history of the Church in the Valley of the Mississippi, a new era in the career of Father Mazzuchelli.

Bishop Loras named as his Vicars-General Father Mazzuchelli and Father Cretin—the former, as the more conversant with the language and the circumstances of the country, taking to himself the task of immediate cooperation with the bishop in the organization of parishes and the erection of churches.

From Galena, where he continued his nominal home, Father Mazzuchelli’s peregrinations were many and far-reaching. He built a residence for the bishop in Dubuque. In Iowa he built churches in Burlington, Maquoketa, Iowa City, Bloomington and Bellevue; in Wisconsin, churches in Shullsburg and Sinsinawa. In Galena he built a second church to take the place of the smaller, constructed some years previously. Vicar-general, he was missionary-general, going far and wide in search of the scattered pioneer for whom none other was caring, to discover hearers to whom, now in simple exhortation, now in stately conference, he might break the bread of divine truth.

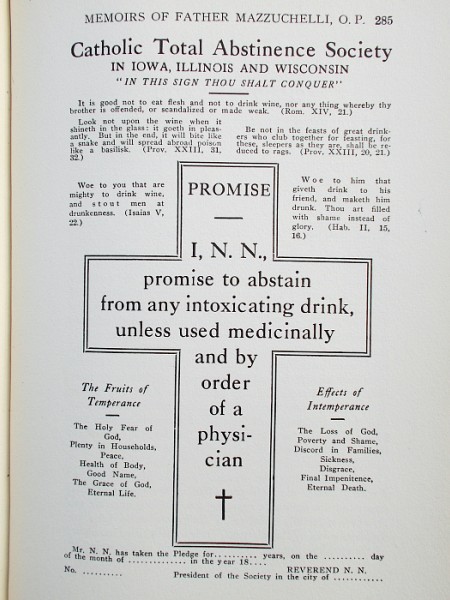

The promotion of total abstinence from intoxicating liquors won his best energy: he advocated it by ready word and loyal example. To every good work, were it hundreds of miles away, he rushed his help. Everywhere he was the welcomed friend. The esteem in which he was held by all classes, the influence civil and social which he was permitted to exercise, marked him not only as the great priest, but also as the great citizen. When the first legislature of the Territory of Wisconsin convened in Belmont, he was the chaplain and was invited at the opening session to address the members on the duties and responsibilities of their fiduciary mandate. The first legislature of Iowa met in Burlington: he persuaded the Senate to hold its sessions in his yet undedicated church, to the enhanced prestige of the Catholic faith, and, no less, to the richer repletion of the parish treasury. Singular, romantic, we well may say, was the missionary career of Father Mazzuchelli, in the variety and the intensity of its activities, in the achievements marking its successive stages.

Another era, this the closing, in the career of Father Mazzuchelli, began in the year 1845. He was back from his visit to Milan and to Rome. Not a long time, as we count time by years, had gone by since, in 1830, he first had seen Mackinac, since in 1835 he first had seen Galena and Dubuque. Meanwhile how wondrous the changes! Now it was the well-ordered civilization of the New World, prosperous today, ambitious of yet higher and better things in the near morrow: it was the Church, with its tens of thousands of disciples, soon to be the hundreds of thousands, organized into dioceses and parishes, under the guidance of a proportionately numerous priesthood. But with the changes were the new needs begotten of the new conditions. Those Father Mazzuchelli could not fail to perceive: resolutely he set himself to provide the remedies.

His plans were three-fold—the organization of a society of specially trained priests, to serve as auxiliaries in the ordinary parochial work and to reach out among Indian and white populations more extensively and more perseveringly than the single-handed diocesan priest could afford to do: the establishment of a college for higher learning for young men: the foundation of a religious order of women pledged to Christian education in whatever form circumstances might counsel. It was a wide and far-reaching programme—perhaps, a too heavy draft on the immediate surroundings—the out-gaze of the great mind, to which the future was visible almost as the present.

A western province of the Order of St. Dominic was thought of, with certain modifications in the existing rule, such as conditions in a newly-settled country seemed to advise. The project went so far as to receive full approval from the Superior-General of the Order and from the Sovereign Pontiff himself. There, however, it stopped. It was too premature, owing to the rarity in those days of vocations to the priesthood.

The college for young men was begun under more encouraging auspices. Buildings were erected at Sinsinawa: Father Mazzuchelli was president and chief teacher: priests and laymen lent him assistance: pupils were in goodly number. Later, in 1849, with a view to its more assured permanency, he confided the college to the Dominican Fathers of the Province of St. Joseph, of Somerset, Ohio. Under their directorship it grew in efficiency and importance, and was giving fairest promise of becoming a great centre of Catholic education, when, in 1866, its doors were closed, the Superior of the Province being no longer able to supply the teachers required by the constantly-increasing needs.

The third project was the foundation of a Congregation of Sisters to serve in the work of Catholic education. To this there came success, ample and enduring. Today it is the Congregation of the Most Holy Rosary of Sinsinawa, Wisconsin. Humble and soul-trying were the beginnings, first at Sinsinawa, later at Benton. Meanwhile, however, a master mind was tracing the outlines of its growth; a master hand was laying deep and solid its foundation walls; courageous women were pouring into it heroic virtues, indomitable patience and self-denial. In this year of grace, 1915, the Congregation instituted by Father Mazzuchelli counts as its membership nearly eight hundred sisters, and amid its works fifty schools, in fifteen different dioceses of the United States, with pupils rising in number beyond the sixteen thousand—chief of those schools, the famed Academy and College of St. Clara.

On his retirement from the direction of his college, in 1849, Father Mazzuchelli took to himself the care of the parish of Benton and adjacent mission stations. The Sisters of the Congregation of the Holy Rosary opened at Benton a novitiate and a school. What time was spared from pastoral duties was devoted to the Congregation and to its school. Father Mazzuchelli was the adviser and the director; and, when need arose, the learned teacher in the classroom.

Father Mazzuchelli passed to Heaven in 1864—dying as befitted his career—a martyr in the service of souls. Suddenly called to the home of a dying parishioner, on a cold wintry day, he had not the time to provide himself with cloak or overcoat. A severe chill followed, and then a fatal pneumonia. As his lips closed in death, the words in Latin were upon them: “How lovely are thy tabernacles, O Lord of Hosts! My soul longeth and fainteth for the courts of the Lord.”

Mazzuchelli was the saint. He was the saint, immaculate of life, scrupulous of duty, exquisite in tenderness of piety—in every attitude the man of God, his every relation with fellow-men revealing the spiritual lucidity of his inner soul, his every act sending forth the fire of love that burnt so brightly within him. This, the testimony of all who had known him, or had known of him; this the uninterrupted rippling of the stream of tradition wherever the remembrance of him survives—the remembrance surviving wherever, even for once, his apostolic footsteps had wended their wearied way.

And what obstacles there were to his saintliness! We recall the unparalleled solitariness of his priesthood, the arduousness of his labors, the uncouthness and the peril incident to his evangelization. He was the youth of twenty-four when bidden into the wilderness. The nearest fellow-priest was hundreds of miles away—savages and savage-like roamers his associates, God his sole prop, his sole helper to sacrifice and courage. Yet he never quivered; he never failed. It is not that he was insensible to the torture of his loneliness. It is pathetic to read, that when saying mass in Indian hut, or under oak-tree branches, he would strive to buoy himself into reverence and exaltation of heart through the memories of the stately temples of Milan and of Rome, and of the splendors of the ceremonies there symbolical of the sublime grandeur of the Christian faith. After Mackinac and Green Bay, it was the rude camp of miners around Galena and Dubuque, or the tent of the wandering immigrant—there again hundreds of miles from a fellow-priest. Yet always he was the saint. In later years, genial companionship was nigher; situations were more generous. But there the piety, the religious fervor of Father Mazzuchelli did not grow in vigor of life; it needed not so to grow; it was what it always had been. If aught else it seemed, it was only the softer mellowness of the autumn enriching the radiance of the preceding spring and summer.

Mazzuchelli was the missionary. With him zeal for the welfare of the Church, for the salvation of souls, was a burning passion. It had sent him in his youth to the wilderness, away from so much that naturally was dear, so much that legitimately was alluring. It remained forceful into the days of old age. Its pathway always was amid hardships and sacrifices. He never sought surcease. Vacation he did not know. Once he went back to Italy; twice he visited his Dominican brethren in Ohio and Kentucky; but important matters connected with his missionary projects, not repose or pleasure, had prompted those journeyings. One business was his—work for souls; to that was given his whole time, his whole energy. His was the device of the Master: “I am come to cast fire on the earth; and what will I, but that it be kindled.”

The zeal of Mazzuchelli was of purest alloy, luminous of unlimited disinterestedness. It was—nothing for himself, everything for God and for souls. Nothing else, he wrote, will commend to Catholics or to non-Catholics, the preaching of the Word so much as real, manifest renunciation of self on the part of the preacher. Telling of his labors in building churches, he makes, as a simple matter of course, the statement that every penny received for his own support, beyond the satisfaction of the most pressing needs, went into his undertakings. He always was the poor man. His human pride, he confesses, did, now and then, rebel against daily dependency on the charity of others; but his spirit of evangelical poverty always won the victory. He lived the poor man, he died the poor man.

Mazzuchelli brought to the service of religion gifts of a high-born and high-nurtured mind. His talents were most varied. As we follow him in the wilderness, we easily imagine what he could have been in the centres of learning and culture of his native land. His “Memoirs” gives sketches of his sermons and conferences. The breadth of thought astonishes, as also the correctness of expression, the poetry of style, the tactful adaptation of exposition to the mentality of his listeners. Nor was scholarship in him limited to matters the more directly connected with religion; it ranged far beyond. No occasion met him of which he was not the master; no requirement made appeal to which he was not adequate—in private conversation, on the public rostrum, in the legislative hall, in the class-room of academy or college. He excelled in appreciation and knowledge of music, painting, and architecture. Of the churches and other religious edifices which he built he himself was the architect; and, so far as his slender treasuries opened the way, the tracings of his pencil did him no small honor. A beautiful altar carved by his hands survives in a chapel in Dubuque. Plans were not seldom drawn by him for civic structures. He was the architect of the first court-house built in Galena, and of the first state-house built in the capital city of Iowa, Iowa City.

Not for the day only did Mazzuchelli think and do. His mind reached much farther into the future. Reading his “Memoirs,” one is astonished at his vision of things to come. The Republic of the United States was to be great among the nations; its western fields were to be the homes of millions; villages were to grow into populous cities. His ambition was to see the Church plant its saplings in a manner that they be the deeply-rooted and wide-spreading trees of future times. His counsel was to secure sites, often quite extensive, for churches and institutions, where as yet the faithful were few, but where growth seemed imminent. Plans he would lay, or bid be laid, for the increase of the priesthood, for the formation of new parishes and of new dioceses. One of the most suggestive chapters in the “Memoirs” is that in which he pleads for the multiplication of dioceses, most aptly noting that present limited resources should not be taken into account, since, he adds, where a self-sacrificing priest finds means to live by, a self-sacrificing bishop would not suffer from penury. No better proof is needed of his foresight than his foundation of a college at Sinsinawa and of a Sisterhood at Benton. At times it was said that he counted too much on the distant future. Be it so; better far the mind that widens too much the perspective than that which unduly narrows it or fain would hold it to present limitations. Perhaps, too, he was over-trustful in believing that men equal to himself in vision, talent and self-denial, were the many, while in fact they were the very few. One thing in his justification—when the future did become the present, it was plainly seen to be what he once had hoped it should be.

Mazzuchelli understood with singular clearness the principles of American law and life, and conformed himself to them in heart-felt loyalty. There lay one of the chief causes of the influence allowed him by his fellow-citizens of all classes, and of the remarkable success with which his ministry was rewarded. He was a foreigner by birth and education; situations in his native Italy were much the antipodes of those in the country of his adoption. Yet he was the American to the core of his heart, to the tip of his finger. He understood America; he loved America. A chapter in his “Memoirs,” notable for its correctness of thought and its lucidity of exposition, is that which bears on the mutual relations of Church and State in the American Republic. As he wrote of those relations so he interpreted them in practical life—seeking under the laws of the land no privileges, sternly, however, demanding the rights they guaranteed.

With all else there went in Mazzuchelli under all circumstances the refinement of social urbanity, the winsomeness of courtly manner, indicative of the thorough gentleman. His presence was a charm; his every attitude was magnetic of attractiveness.

Mazzuchelli was to the end the priest and missionary. Once, certainly, if not oftener, the higher office of the episcopate was within his reach: his humility and fear of responsibility led him to repel it. A letter he addressed in 1850 to Bishop Loras is preserved in the archives of the College of Dubuque. In this letter he writes: “My present situation (in Benton) is more pleasing to me than any I have had before in America, and it would be a great sacrifice to leave it even for a bishopric. … To live retired and unknown to the world is a great happiness. … If the Lord is not very much displeased with me, he will permit me to work in oblivion before the world and enable me to know him more and more. Amen.”

A great man, a great priest, passed across our land in the person of the pioneer missionary—Samuel Charles Mazzuchelli. His name will always be cherished in fondness and gratitude.

Better than what other pen may write of him is the tracing of Samuel Charles Mazzuchelli’s own pen.

I speak of the book—”Memoirs, Historical and Edifying, of a Missionary Apostolic of the Order of Preachers, among Tribes of Savages, and among Catholics and Protestants, in the United States of America.”

The book was originally written in Italian, and printed in Milan, in the year 1844, during the visit of Father Mazzuchelli to his native land. It was his duty to give to his superiors in Rome a faithful account of his journeyings and doings in far-off regions, and it was also his wish to awaken an interest in his field of labor with the hope of obtaining for it missionaries and financial help. Both purposes were served by the story of his work. It must appear strange that this volume has remained until now hidden from the American public—so valuable it is as a contribution to the history of the Church in America, so alluring otherwise in theme and in form. At last it has found a translator—a member of the Dominican Sisterhood of the Congregation of the Holy Rosary of Sinsinawa. To this talented and industrious woman Americans, American Catholics particularly, owe a deep debt of gratitude.

The sole regret the volume evokes as we turn over its pages is that it did not have a successor in another volume from the pen of its author, Mazzuchelli, giving the narrative of his life and labors subsequent to the year 1844.

The “Memoirs” comes as the voice, veracious and musical, of the long ago, telling of our early apostles, how they lived and wrought, how they built and planted in order to leave to us the heritage that today is our joy and our pride.

It is a picture, in absolute faithfulness, of Father Mazzuchelli and of his work; consequently a picture of entrancing beauty. No other pen than his own could have traced, in their every lineament, his personality and his work; none other could have known him so well as he was known to himself. None other could have made the picture so beautiful; an attempt to improve upon realities were to lessen their splendor; none other could have been so careful to forbid the attempt. In writing he was utterly unconscious of self. Nowhere in the book is his name seen, not even on the title-page. He is simply the “Priest,” the “Missionary.” The book is altogether impersonal. The reader, not otherwise informed of its authorship, might well question who the hero is of whom discourse is held.

As a historical document the “Memoirs” is of exceptional value. It tells of a wide region of territory—from the waters of Huron to those of the Mississippi and the Des Moines—exactly as it was in the days of its wilderness and of its first entrance into civilization. The populations that tenanted its forests and prairies—the Ottawa, the Menominee and the Winnebago, the fur-gatherer and the trader, the incoming land-seeker and the town-builder—rise from its pages in full native vividness. The reader is brought into immediate touch with them, made to mingle in their daily doings and manner of life. It is precise and exact in dates of years and of months, in descriptions of men and of events.

As we should have expected, the chief theme is the work of the Catholic missionary—the hardships it imposed, the hopes it begot, the virtues of soul it exacted and embellished. But the general civic and social life is not overlooked. The writer was a keen observer of incidents of every nature, and a faithful narrator of what he saw and heard. Few, indeed, were the incidents in which he himself was not a sharer, as priest or as citizen, and in describing himself he describes the several current activities of his time. No fervent student of American history will be without a copy of the “Memoirs” on the shelves of his library-room.

The translation of the “Memoirs” from Italian into English merits high praise. It evidences a thorough knowledge of the two languages. It has the primary quality of every valuable translation—it is faithful to the original, in meaning of words, in poetic flow of diction and, what is of no lesser importance, it presents itself to the English reader in a literary style that is always correct and graceful.

TRANSLATOR’S PREFACE

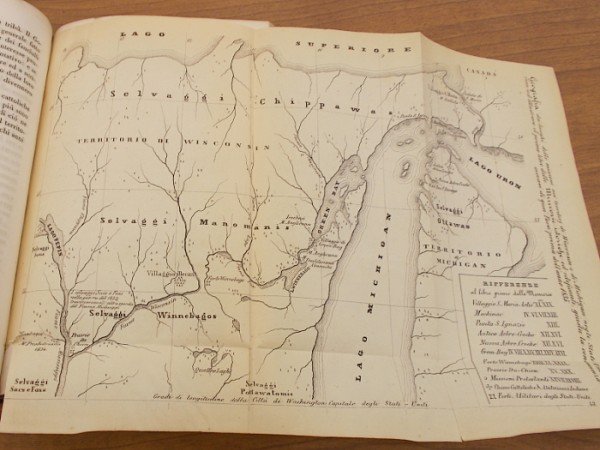

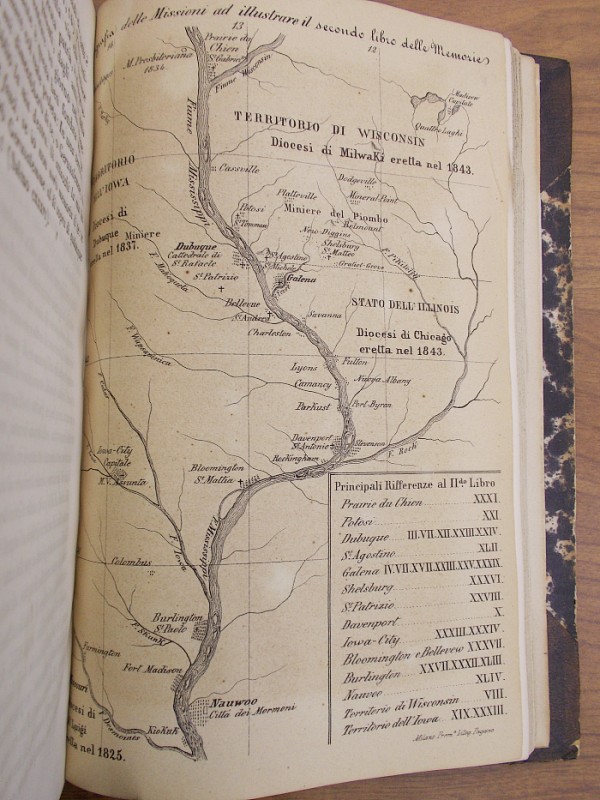

This book, familiarly termed the “Memoirs of Father Mazzuchelli,” as the readiest adaptation of his own Italian term “Memorie,” is not an American book in the usual acceptation of the term; yet, though written in the Italian language, every line concerns itself with the people, the customs and the institutions of these United States, particularly from the standpoint of an educated, intelligent foreigner inspired with the highest missionary zeal for the cause of God and souls, and at the same time an ardent admirer of this great Republic and with a prophetic vision of the place it was to occupy among the nations. It was probably written in Milan, his birthplace, on the occasion of his only visit there, in 1843, and the following year was certainly printed and published there, with elaborate maps of America drawn by his own skillful pen (the fac-similes of which it has seemed best to preserve) by the publishing house of Boniardi-Pogliani.

The work is divided into three sections designated as Books. Book I treats mainly of Father Mazzuchelli’s Canadian, French and Indian missions and conversions.

Book II gives a history of his mission work among both Catholics and non-Catholics in Iowa, Michigan, Illinois and Wisconsin, of the building of many churches in these territories necessitated by the increase of immigrants, and of the creation of the Diocese of Dubuque. This book gives some valuable data in the civic history of 1865.

Book III is a thoughtful account of religious conditions in the American Republic.

The translation of this work from its original Italian into English presented a peculiar difficulty. Aside from the utility of the book, it is so full of incident, with such careful attention to time and place and sequence of events, that, in the right hands, a free translation might result in a pleasing and valuable acquisition to the history of the American Church. But in this case no departure from a literal rendering is permissible. The author of the work was a saintly priest, than which dignity there is no higher: a missionary of the Order of Saint Dominic, whose motto is “Veritas.” Therefore even at the risk of grave injustice to the original, and to avoid the yet greater risk of falsely coloring, ever so faintly, even one word—representing the soul of this true type of the modern apostle of the nineteenth century, Father Samuel Charles Mazzuchelli, O.P., this rendering of his book into English has been left with all its peculiarities of construction, as closely parallel to the original as a translation permits.

Sister Mary Benedicta Kennedy, O. S. D.

Saint Clara Convent, Sinsinawa, Wisconsin.

Feast of the Assumption of Our Lady, 1914.

MEMOIRS

OF THE

VERY REVEREND

SAMUEL CHARLES MAZZUCHELLI, O. P.

MEMOIRS

OF A

MISSIONARY APOSTOLIC

OF THE

ORDER OF SAINT DOMINIC

TO THE READER

Among the motives that persuaded the compiler of these memoirs to consent to their publication, there are two leading ones: First, to comply with the earnest solicitations of many pious persons in Italy, both of the laity and religious of the illustrious Order of Preachers to which the missionary glories in belonging, who have expressed the most eager desire to obtain a more thorough knowledge of his labors in a region little known in Europe, and where, thanks to Divine Assistance, he was able to establish Catholic worship; the second motive he considers as of grave importance, also, as it is with the design of contributing to the Ecclesiastical history of the United States of America, those documents which will one day assist to make clear the beginning of the dioceses of Detroit, of Milwaukee and of Dubuque, recently erected by the Sovereign Pontiff, happily reigning, and make known the obstacles which the servants of the Lord have to encounter in the propagating of the truth of the Gospel.

It is to be hoped that this little work which may tend to the edification of some, and may powerfully move the zeal of others for the propagation of the Faith, will redound also to the greater glory of God, which is the only aim proposed by him who writes.

It has been thought useful to preface the book with a few thoughts concerning the vocation to the holy missions, and a simple account of the circumstances which attended the same vocation of the person in question, for the benefit of those who feeling called thereto, delay in responding either through misplaced apprehension or for any other reasons. For the better understanding of the subject, and in order not to deviate from the form of a well-conducted narration, although facts and places varied in many respects are treated of, it has been thought best to describe them chronologically, and thus relieve the monotony of the account.

Honorable mention has not been omitted of the missions of other priests which were near those of the missionary, not only to render them their just meed of homage, but also that there might be no break in the history of those countries. The compiler would be more diffuse in his description of the missions which in some places preceded those of the missionary, if the accounts given by the old inhabitants of certain places had shown a higher degree of probability.

Actuated solely by the thought of helping others, he has intermingled with his own narrations certain moral reflections that sprang from a heart accustomed to derive from all happenings that which makes the blessings of Divine Providence and the sublimity of the Christian virtues shine forth the more resplendently.

The name of the missionary and the circumstances of his life not connected with the history of his labors, are withheld as is fitting, since they are considered of no importance to the object of these memoirs, who looks upon himself as but a simple instrument of the Will of the Lord.

If any should wonder that the Annals of the Propagation of the Faith have not published at least a portion of these memoirs he must bear in mind, in the first place that not everything which is effected by the missionaries in foreign countries can be known by that wonderful Association which is beyond praise; and moreover, that there are priests who by reason of their great distance from Italy, or the precarious conditions surrounding them, or lastly, perhaps, willing to put into practice the Evangelical Counsel, to let not the left hand know what the right hand doeth, fail to set forth their deeds in public. We are to consider, however, that our Lord counseled us to make known our good works and glorify our Father Who is in Heaven (St. Matthew, V. 16); He Who graciously disposes all things, has appointed in His inscrutable ways, the time, when, with Christian prudence, not through vainglory, or through any other human motive, it will be fitting to reveal His works. It is to be hoped that the simplicity of these narrations will atone for the absence of an elaborate or pleasing style which seems hardly suitable to one who is describing a religious mission for the purpose of spreading the truth.

Everything that is found in this little work has been conscientiously written down, with nothing exaggerated, and if among the pictures presented, one does not meet with the marvelous and the supernatural which some writers imagine to be inseparable from the history of the missions in these remote regions, that will serve to correct the erroneous idea given by those writers, who in order to give a more vivid color to their narrations have often allowed themselves to be carried away by too great a taste for the romantic.

May God grant that these few pages may arouse in the hearts of kind readers an unceasing desire to co-operate in the propagation of that Faith which is the most precious gift of Heaven in correspondence to which it would be a little thing to sacrifice all the goods of earth and even life itself.

BOOK I

Memoirs of Missions Among Various Indian Tribes and Among the Canadians in the Territories of Wisconsin and Michigan

MEMOIRS

CHAPTER I

THE VOCATION OF THE PRIEST TO THE PROPAGATION OF THE FAITH.

If in the world each one is called by Divine Providence to fulfill those duties which constitute the various occupations of life necessary to the formation and progress of human society, it is no less true that among the Priests of the Sanctuary of the Living God,—He Himself has distributed the administratioa of the graces of Redemption which form the Society and Communion of Saints. In the very creation of the heavens, the Omnipotent has ordained that the individual marvelous revolution of each sphere should form but one part of the beautiful universal unity, worthy of the Being, One and Infinite. The spiritual work of Christ is no less grand, no less worthy of Him Who said in the beginning “Be It Made” and all was made, while Saint John declares that all things came to pass through the Word, and without Him was made nothing that was made.

It belonged to Incarnate Wisdom to so order His mercies in order to provide for the wants of every nation and every grade of human conditions, and to supply the impotence of those who were to be the dispensers of these mercies even to the end of time. Although man may have attained the sight of only a very few of those secret, divine ways, through which the blessing of Redemption is offered to all mankind, what Saint Paul wrote to Timothy is certain, that God our Savior “will have all men to be saved and to come to the knowledge of the Truth.”

He Who came to save sinners and to provide for all, the means for eternal life, has so ordered the sublime duties of the ministry of His House, that to some He gave Apostolic zeal that they might go forth and bring forth fruit and that their fruit should remain; others He enlightened with Heavenly wisdom against which the enemies of Truth cannot prevail. Many received from the Giver of all good, the power to seal with their blood the divinity of their holy ministry, and they proved that the gates of hell will never prevail against the Faith. Yet others with the gift of miracles have called the nations from the darkness of idolatry to the light of the Gospel. He who has glorified the Heavenly Father with piety and good works, who has burned with desire for the salvation of souls; and they that instruct many to justice shall shine as stars to all eternity. Dan. XII-3. Many zealous for building churches, can say with David, “I have loved, O Lord, the beauty of Thy house and the place where Thy glory dwelleth.” Psalms XXV-8. Many consecrated to the Sanctuary were called by Divine Providence to the care of the poor, the sick and the ignorant, that they might be the benefactors of suffering humanity. In fine, the needs of individuals, of society and of the entire human race have felt the saving influence of Him Who came for all mankind.

The ministry of Christ our Redeemer is so ordered that the great variety of duties and the distance of time and place instead of keeping souls apart, bind them together yet more closely in the bonds of perfect unity; for those duties are like the waters springing from one and the same divine source, refreshing by their branching streams the aridity of humanity, and leading it on to the ocean of Divinity itself,—its only Good. When the Word Incarnate said: “One is your Master” He suggested the grand Catholic truth that however the operations of the sacerdotal state may be distributed among the many who are called upon to succor this or that particular necessity, yet He Who teaches is One alone, God Himself, from whom spiritual power proceeds. In the Catholic Church the unity of the sacred ministry shines forth like the light of the sun, for there the manifold operations of the Apostolate are stamped with the same visible authority, without which everything would be isolated and powerless. If ignorance, the offspring of vain human learning, did not blind the intelligence, even men of the world at the sight of that apostolate which embraces so many centuries, all societies and all conditions of life, would cry out at least, with the false prophet Balaam: “How beautiful are thy tabernacles, O Jacob, and thy tents, O Israel!” (Numbers XXIV-5.)

While sure of being with Christ in the holy ministry, it is of the highest importance to the Priest to ascertain to what duties he is specially called. The daily happenings of life are the ordinary means which little by little manifest to him His own special mission in the kingdom of Christ on earth. To desire to select absolutely one mode of entrance into the sacerdotal state notwithstanding the lack of those gifts which are required therein would be to call one’s self, while our Redeemer said: “You have not chosen Me; but I have chosen you and have appointed you.” (John XV, 16.) He who takes upon himself a holy duty for which his incapacity unfits him, bears the full weight of a divine, eternal responsibility and ordinarily brings forth no fruit which remains. But when Christian prudence permits us to believe ourselves endowed by Almighty God with certain qualities, exacted for the fulfillment of the obligations annexed to the sacerdotal state, then one may reason that he has been called thereto. An upright intention, purity of conduct, docility towards him who has the spiritual direction of our souls, prepare the way for the manifestation of the Will of God, which manifestation if it does not become absolute certainty, is at least that moral probability which can never be accused of imprudence, and which ought to serve as a guide to the most timorous conscience. Absolute certainty of our vocation has never been granted through ordinary means, although we may be allowed to believe its existence, when time and results have, so to speak, proved the reality of one’s election.

Few have that generous disinterestedness in their choice of the varied duties incumbent on the priesthood, which moved Saint Peter and the Apostles to abandon human interests, which often seem determined to oppose the call of Heaven. The sublimity of this career, however, is so great a boon, that the refusal to follow it, on account of any human attachment whatsoever, would render us the objects of those terrible words of Christ: “Every one of you that doth not renounce all that he possesseth, cannot be my disciple. (Luke XIV, 33.)

Of all the duties of the priesthood that of the Propagation of the Faith among peoples who know naught of it, is the most excellent and meritorious. He who fulfills this evangelical mission, together with the example of a pure life and good works, and the continual preaching of the mysteries of salvation was expressly commended by the Apostle when he wrote to Timothy: “Let the priests that rule well, be esteemed worthy of double honor; especially they who labor in the word and doctrine.” But when a priest is called, as was the Prophet Jeremias by the voice of God Himself, and assured that he has been sanctified and made a prophet unto the nations, he could in truth make answer: “Ah, ah, ah, Lord God: Behold, I cannot speak, for I am a child.” In fact, who will believe himself, I do not say worthy, but even able to be made “a minister according to the dispensation of God, that I may fulfill the word of God. The mystery which hath been hidden from ages and generations.” Who will be able to have made “known to him the riches of the glory of this mystery among the Gentiles?” (Col. I.) With reason then did Jeremias call himself a child at the sight of so great a mission. But the Evangelical word is the work of Christ,—it has naught in common with human ignorance and the wisdom of this world; as the Apostle says: “The foolish things of the world hath God chosen that He may confound the wise: and the weak things of the world hath God chosen that he may confound the strong,” (I Cor. I, 27), and he also gives the most convincing reason for this truth when he adds “that no flesh should glory in His sight,” v. 29.

One who is called to the ministry of the word should like the Prophet often humble himself in the contemplation of his own incapacity and childish ignorance, for even the most profound studies in sacred doctrine become unfruitful in the mouth of the most eloquent, without that divine inspiration of Him Who is the way, the truth and the life. The sublimity of speech and of human wisdom did not accompany the coming of Saint Paul among the people of Corinth, but, as he himself says, the knowledge only of Jesus Christ and Him Crucified, that their “faith might not stand on the wisdom of men but on the power of God” (I Cor. 2, 5.) By virtue of the Cross alone ought the Priest Apostle, with the lively faith of Saint Peter let down his net into the troubled sea of this life; sure that sooner or later his Divine Master will make him an instrument of salvation to many. Vainly would one enter upon an apostolic career, even in regions most remote, buried in the darkness of ignorance of Christian truth, or blinded by the errors and extravagances of heresy, unless with an entire self-abandonment to Him Who has said: “Going, therefore, teach ye all nations. Behold I am with you.” Matt. XXVIII, 19. The foolish fear of lacking the necessaries of life would be a want of faith in the Son of God Who gave us this command: “Be not solicitous, therefore, saying What shall we eat or what shall we drink, or wherewithal shall we be clothed?” (Matt. VI, 31.) Amid doubts such as these what would become of the faith of the ambassadors of Christ? The holy Gospel assures us that our Heavenly Father Who feeds the birds of the air and arrays the lilies of the field with a splendor more dazzling than Solomon’s will have a care to give His laborers their hire. Let them seek first the Kingdom of God and His justice and all these things shall be added unto them. This is the promise of our Redeemer to missionaries of the Gospel: whoever doubts it has little faith and in truth is unworthy of the Apostolical ministry.

The comforts and riches of this present life should be despised by one who has left all things, in order to say with Saint Peter to the Divine Master: “Behold we have left all things and have followed Thee.” (Matt. XIX, 27.) He Who has promised to give for one such renunciation a hundred-fold in this world and life eternal in the next, will provide for every need. The preacher of the Gospel may apply to himself what Christ declared on this subject to His Apostles: “The laborer is worthy of his hire. … and into what city soever you enter, and they receive you, eat such things as are set before you.” (Luke X, 7-8.) The grace of Providence shall go before him, disposing the hearts of the people in various ways to minister to his needs, that one may recall these words: “When I sent you without purse and scrip and shoes, did you want any thing?” (Luke XX, 35.)

Such should be the mien of him who preaches the truth confirming it with the brightest example: charity, zeal, disinterestedness, piety, modesty and patience should make of him a living image of his Divine Master, Who set example before precept. Then will be verified in him those words of Holy Writ: “How beautiful are the feet of them that preach the Gospel of peace, of them that bring glad tidings of good things!” (Rom. X, 15.)

Placing obstacles to the vocation of a person who is well qualified and desirous of dedicating himself to foreign missions is to oppose one’s self to the Divine Mercy of our Saviour, who, “seeing the multitude, had compassion on them: because they were distressed and lying like sheep that have no shepherd. Then he said to his disciples: ‘The harvest indeed is great, but the laborers are few’ ” (Matt. IX, 36, 37.) The consequences of such opposition are dangerous, both for him who hears the call and for him who hinders: for the desire of a close yet brief companionship and the fear of a temporary separation upon this earth might draw down tribulation and chastisements in this present life and everlasting separation in the next: then would be verified that word of Christ: “A man’s enemies shall be they of his own household.” (Matt. X, 36.)

In place of putting stumbling-blocks in the way, parents and friends ought to glory in seeing their nearest and dearest dedicate themselves so particularly to the propagation of that same Faith which they themselves have received through no merit of their own, and for which they can never sufficiently thank God. It might here be remarked that one of the principal reasons why so few consecrate themselves to the Apostolate is the lack of reflection among the clergy in Catholic countries upon the pitiable condition of those nations who have not received the truth of holy religion. Many priests born and educated in the unity of the Faith have never had the experience of feeling to the quick that anguish of heart inflicted by the sight of the destruction of souls mid the darkness of ignorance and heresy. Ah! if they would but know the gift of God, the blessing of being born in the abundance of spiritual riches, of sitting at the Eucharistic Table every day, of frequenting the House of God at their pleasure, of having ever ready to hand the divine remedies for the cure of every spiritual malady, in a word, of enjoying in their degree all the mysteries of the goodness and greatness of our Redeemer, the while many nations are yet deprived of these blessings, then would they feel a more efficacious zeal burning within their hearts, and not content with merely compassionating from afar the miseries of others, would put their hands to the work, mindful of that command of Christ: “Go, teach all nations.” God grant that no priest imitate that rich man, who, surrounded by all the good things of this world, contents himself with desiring necessary food for the famished poor, while he himself is too tardy and too avaricious to supply their needs. It should be the glory of Christ’s servants not only to hear His call, but to be in reality the instruments for the propagation of the Gospel, the light of the world.

It is almost incredible that the goods of this life,—parents, friends, love of country, and worse, love of riches, can be to any a hindrance to the Apostolic vocation. Motives of such a nature would shame even one who is willing to sacrifice the very least of the gifts of Heaven, and would show a littleness of soul, of which it is better not to speak, that we may disclaim the very supposition that there exist any individuals in the divine career of the Priesthood who are willing by like weaknesses to belittle such career. Preaching the Faith is a work so meritorious, so worthy of the clergy, so like that of the Messias, that it should revive the noblest sentiments of the heart and produce a superabundance of Evangelical laborers, yet Christ tells us the contrary: “The harvest indeed is great, but the laborers are few.” (Luke X, 2.) Let us rouse ourselves then, and let us open eyes of Evangelical charity, and if we are called, let us direct our steps wherever the work is great and difficult, but where also with the help of Him Who sent us, we shall open the ways for the Gospel and where through Him our labors and fatigues will meet with success according to the certain word of Saint Paul: “I have planted, Apollo watered: but God gave the increase.” (I Cor. III, 6.)

CHAPTER II

THE DEPARTURE AND VOYAGE OF THE MISSIONARY OF THE ORDER OF PREACHERS FROM ROME TO CINCINNATI IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA.

Not without difficulty is it for an ecclesiastic departing for the country of his missions, to bid farewell to parents and friends, and native land, and set out towards that region to which the Lord has destined him, for the salvation of others, and for his own sanctification. This material separation does not hinder his bearing with him that sincere filial and fraternal love towards those who have done so much for his education and have a natural claim upon his heart. Yet under such circumstances one ought not to reflect upon the material aspect of the separation from beloved friends and native land, but he ought to have before his eyes the sublime, divine motive which breaks the strongest ties of nature in order to make of them a sacrifice to the will of Heaven. To the flesh such a farewell seems cruel and unjust, but to the spirit of the Christian it becomes sweet and mild, for it is the yoke of Christ. Such was the case of a son, who for the last time embraced a tender father who on every occasion had shown his predilection for him, and who, five years before had besought his son to stay and one day close his eyes. But of what avail could this strong tender love of a father be to one who willed to renounce the world and take upon himself the discipline of a cloister? Could it silence the voice of Heaven and draw aside from his vocation one who felt himself interiorly called to separate from the world, and who believed that he would openly resist the Will of the Lord, if he listened to the allurements of flesh and blood? Thanks to the Giver of all good, these whisperings excited by the pleadings of a father’s heart were calmed by the words of Christ: “He who renounced not father, mother, brothers and sisters cannot be my disciple.”

In 1828 when obedience destined our missionary for the United States of America, he left Rome, and revisited his native city of Milan after five years absence. Then the farewell to father, beloved sisters and dear brothers was made with all that tranquillity, which the certainty of doing the will of God could secure. The affection and the duty towards parents are not at all diminished by such occurrences in the life of a Christian; a son fulfilling his mission upon earth, renders to his father that true and just recompense which is due for all the cares and anxieties spent upon his education. A father should consider himself happy to see his sons follow out the career assigned them by divine Providence; since in such case only do they correspond to the purpose of their birth in the world, and recompense the labor spent in forming them to virtue and eternal life.

When the last farewells were over, he left his native land with little hope then of ever seeing it again, and yet without overwhelming grief of heart. In truth we have no lasting home on earth; a Christian’s native country is wherever God calls him; therefore for the man called to the Apostolic ministry the fact of leaving the place of his birth to go into missionary countries was rather a setting out in search of his own country. On the other hand he who departs for an object worthy a disciple of Christ, accustoms himself to consider the whole world as his own country because his affections are in no wise circumscribed by the limits of one city or by the boundaries of a kingdom, but more widely do they extend over the vast number of nations and the boundless seas; so that in this sense also the word of Christ seems to be verified wherein He promises us a hundredfold for what we have given up. Behold, a hundred cities, a hundred nations under different skies become our magnificent fatherland. Oh, how generous is our God! The friends, then, the companions, left behind in that narrow corner of the world which has seen us born into the world and grown to manhood! O, they are not lost, while a sincere affection for them can be and ought to be kept alive; and meanwhile the missionary as he passes on to new lands, goes to find new friends, to increase the number of them and to multiply the consolations of Christian friendship, and because the chains that bind them together in the propagation of the truth of the Gospel are not the work of chance but the fruit of virtue, it follows that such friendships are nobler, more lasting than those of our youth. So does God reward in full, that transitory anguish inflicted by the separation from parents, friends, native country; Almighty God is not outdone in generosity; He never accepts the smallest sacrifice from a human heart without pouring upon it His divine munificence in abundance even in this life.

The journey of a missionary to the country that Divine Providence has appointed to him is always accompanied by circumstances from which he may derive many experiences useful for the fulfilment of his ministry,—more especially in acquiring that necessary confidence on which he must lean in future needs. Such were the lessons that he learned during his passage from Rome to the city of Cincinnati in the United States of America. The visits made to the churches and sanctuaries of Florence, Bologna, Milan, Genoa, Lyons, Paris, and to the Capital of the Catholic world, monuments which down the ages have been the glory of Religion and Art, had yet more deeply impressed upon him that veneration and spirit of piety which should accompany every act of the Christian, yet more of him who is called to preach the truth of the Gospel.

Experience has taught us that when God’s minister finds himself alone, without a church in the country of the infidel, deprived of all external objects that promote piety, the holy remembrance of things that he has seen in the midst of Catholic surroundings supplies in part the want of such reminders. On such occasions, memory vivified by Faith, bears the lonely spirit into the temples of the Living God, before our tabernacles where, to Jesus in the Blessed Sacrament, are rendered those honors by which man manifests the secret desires of his heart. In truth when he was in the forests and vast solitudes of the heart of North America often did he imagine himself present at the sacred rites of the European Churches, joining in the solemn canticles of Divine Worship. His imagination of itself turned to those sacred objects, when he was obliged to celebrate the Holy Sacrifice in a log hut, or in the wigwam of a savage, upon an altar not deserving even the name of table,—sometimes constructed of the bark of trees.

Almighty God even made use of the memory of His temples to excite in one an ardent desire to build them wherever the Catholic Faith spread. It was impossible to express in words the holy anxiety which wrung his heart and overcame the great difficulties involved in the building of a Church, an anxiety in great part caused by his having seen in Catholic countries the vast number of churches and sacred ornaments in all their magnificence. In truth, at times it seemed to him that things belonging to the service of the Holy Sacrifice were not impartially distributed; he used to say to himself, that in some places, Catholics had a superabundance of everything to be desired and that here where the need is greatest they do not possess even the things most indispensable for Divine worship. Making one’s self familiar, therefore, with everything great and sacred in Catholicity will ever be of the greatest advantage to one setting out for distant missions, for it will assist his piety when, lonely and deprived of the sight of God’s temples, the memory of them will fill the void in his heart, in a measure; it will give an impulse to his zeal for the building of churches, notwithstanding the many and serious difficulties to be overcome by one who puts his hand to a work so necessary for extending the Faith and the worship of the true God.

But let us follow our traveler. After making the journey from Rome to Lyons with the Vicar-General of Cincinnati, he was left there alone at the end of July, to make his way towards the new world. Somewhat of fear and doubt made itself felt in such a situation, putting to the proof his vocation and his confidence in Almighty God’s disposal of him. The idea of setting out alone for a far-off country, on the other side of the Atlantic, without a knowledge of the language of its inhabitants, to a youth of twenty-two without experience, would have been rather imprudent had it not been justified by religious obedience, that obedience which would be a safe guide in traveling to the end of the world, if that were necessary. In reality, if a religious man takes holy Obedience as his guide during the great, mysterious journey from this world to the immense eternal regions of God’s Kingdom, how can he doubt that Obedience will conduct him safe back and forth to any quarter of this little globe of ours? See how the vow, folly in the eyes of the world, by its power overcomes worldly wisdom itself and inspires that courage and energy of soul that will be sought in vain elsewhere.

The Lord so disposed events that our Ecclesiastic was obliged to prolong his stay in France for two months, in the little Seminary of Saint Nicholas, where the charity of the Superiors had offered him an asylum. Such delay was of the greatest advantage, since during that time practising with the good seminarists then enjoying a vacation, he learned the French language, an acquisition which after his ordination to the priesthood became indispensable in the exercise of his ministry. While he was anxious concerning the great loss of time in regard to his long journey, the result convinced him that he could not have spent those two months more profitably. Thus do accidents which seem adverse often co-operate for good and serve to make ready God’s ways hidden from us! Moreover this proves that we must always believe there is some design of Providence in the involuntary delays which so often happen in traveling.

On the fifth day of October, 1828, were unfurled the sails of the American ship, the “Edward Quesnel,” in which our young Ecclesiastic had secured his passage to New York, and he left the shores of Europe in the firm hope of seeing, when it should so please God, the lands discovered by Columbus. For some days the winds were contrary, and as if jealous of their dominion, refused to permit the ship a peaceful passage across the immensity of the sea. But the fury of the elements calmed down at last, and a favorable breeze from the east sped the barque towards the longed-for harbor. It was a pleasant sight to see on a clear day, all the sails full-spread, the sea peaceful, the sky pure and serene, companions joyous and full of hope, making their calculations on the day in which they flattered themselves they would happily reach port. Like to this is the living, true image of those thoughtless men, who, founding their happiness upon the uncertain things of this world, dream of future pleasures which prove in the event to be naught but shadows and illusions. In fact fleeting was the joy of the sailors; the winds howled both from north and west; the ocean’s billows rose threateningly, and the ship was forced to rise and plunge with the troubled foaming waters; the rigging could barely resist the fury of the wind and mitigate the motion of the tempest-tossed craft; then all became silent in the saloon, for he was fortunate who could keep himself steady in his couch. The missionary in spite of the tempest enjoyed the sublime sight of the ocean, when unchained and storm-driven, it seemed to have sworn the destruction of the man who defied its wrath. Clinging to the main-mast he could see the broken, imperious waves venting their wrath upon the ship, often as if striving to engulf it, flooding the deck with their crest, but conquered by man’s power, breaking and passing off, the wind howling unceasingly among the masts and cordage seemed to predict death and ruin. The heavens all darkened, crashing with thunder, denied to the gaze of the voyager even the slightest gleam of hope for safety. The missionary’s imagination, stirred by this spectacle so really frightful, involuntarily was borne on to meditate on that last catastrophe described by the eloquence of the Son of God:

“And there shall be signs in the sun and in the moon and the stars, and upon the earth distress of nations, by reason of the confusion of the roaring of the sea and of the waves:

“Men withering away for fear and expectation of what shall come upon the whole world.” (Luke XXI, 25, 26.)

A favorable wind succeeded the storm and already on November 7th the sight of land gladdened the hearts of the voyagers, but vainly, for the wind suddenly changed and blew from the west with such fury that one might have said the ship had taken flight to Europe; thus for five days she was driven backward over the wide sea, until the Supreme Ruler of the waves set her again upon the right course, and on the morning of the fourteenth she calmly neared the wished-for coast. Ah ! when men are agitated by stormy passions in the dark night of this vale of tears, if they but knew how to use that tireless industry, perseverance and patience taught us by the mariner! then would all arrive at the port of eternal salvation.

Some days of delay in the great city of New York, convinced our traveler that the grand things of this world are ever in close relationship with the general corruption of morals; thence he passed on to the beautiful, beautifully planned city of Philadelphia, and from there to the Archiepiscopal city of Baltimore. During this short journey, he realized the great inconvenience of not knowing the English language, and of being forced like the Patriarch Joseph in Egypt to hear a language that he understood not. There yet remained about eight hundred miles of a journey, partly by land, partly by water, before reaching Cincinnati, the place of his destination; he was without a companion who spoke one language known to him, and moreover uncertain whether the money at his disposal was sufficient for so long a journey; yet he leaned upon Divine Providence, greater than all treasure. On the first day that he spent in the stage-coach an American gentleman perceived his extreme embarrassment in the offices and taverns on account of his inability to make himself understood and touched with compassion towards the stranger gave him to understand by signs that he himself would have everything paid for and attended to both by land and by water as far as Cincinnati, and that there the sum expended would be shown to him. In short from that morning the young Ecclesiastic had nothing to do but take his place in the carriage, to go to the steam-boat, or seat himself at the table whenever he was called; so in a few days he reached the place of his destination. His kind protector then wrote upon a card the sum paid out for him on the journey; but perceiving that the poor European had not sufficient money, he smiled and made him a sign just to go to the Catholic Church, which building was seen not far distant. Who would not in such case have given thanks with all his heart to Divine charity for the particular protection under which that charity had so happily led him to the end of his long journey! Had he not reason to say with the holy Tobias: “He conducted me and brought me safe again; we are filled with all good things through him”? (Tob. XII, v. 3.)

CHAPTER III

STUDY OF THE ENGLISH LANGUAGE. VISIT TO THE CONVENT OF SAINT ROSE, PREPARATION FOR THE PRIESTHOOD IN THE CONVENT OF SAINT JOSEPH, AND ORDINATION TO THE DEACONSHIP AND PRIESTHOOD.

Monsignore Edward Fenwick of the Order of Preachers was then the venerable Bishop of Cincinnati; it would not be easy to describe the sweetness with which he welcomed his young brother in the Religious vocation and his kind concern to have him instructed in the language of the country. Our Ecclesiastic devoted the time up to the Feast of Christmas to mastering the principal difficulties of the language, when the Bishop desired him to make a visit to Saint Rose’s Convent of the Order of Saint Dominic, in the state of Kentucky, distant about two hundred miles from Cincinnati. Having reached Louisville, a commercial city of that state, he was obliged to continue his journey on horseback, and to travel thus thirty-eight miles without resting. It was the missionary’s first riding-lesson, and was so dear a one, that when he finally arrived at Bardstown, then the residence of the Bishop of Kentucky, he was obliged from extreme fatigue to keep his bed for two days. But it was a lesson most necessary for one who was afterwards to undertake long journeys on horseback to places where for many years there was no other means of traversing the country. His strength returning after some days, the Bishop, Right Reverend Benedict Joseph Flaget honored him with the loan of his own horses and a guide to take him the distance of fifteen miles where the convent was situated. This is one of the oldest religious foundations of Kentucky; the first asylum of the Dominicans in the United States, and the first college of the state; there were trained many priests, among them the present Bishop of Tennessee, Monsignore Miles of the Order of Preachers. The Church of Saint Rose is large and much frequented by the surrounding people. The convent is quite large and capable of containing a goodly number of religious. The community derives its subsistence principally from the land which was purchased for that purpose when the Order was first established here. Not far from the convent is found a convent of religious women of the same Order, devoted to the instruction of young girls: in this way the religious are most useful for the propagation of the Faith and cultivation of the mind. When the young ecclesiastic returned as far as Bardstown about the first of February, he was obliged to remain there, for the Ohio River, on account of the ice, was not navigable to Cincinnati. A happy circumstance for one who was glad to profit by such a delay! The gentle, holy companionship of the holy Bishop Flaget was enough to inspire piety and apostolic zeal; ever active, yet kindly with every one, while he won hearts, he inflamed them with the love of God and of the salvation of souls. Lessons such as these are not easily forgotten.

There lived at that time at Bardstown the very reverend Patrick Kenrick, at present the most worthy and learned Bishop of Philadelphia: he was then professor of theology in the seminary of that diocese. His guest having been present at several of these lessons was not a little surprised at the ease and clearness with which he imparted the truths of holy doctrine to the young: under the priceless mantle of humility, he concealed those superior qualities with which the Almighty had endowed him. The missionary may be permitted to relate this circumstance to the honor of the priesthood and the confusion of modern philanthropists; that one evening on entering the Professor’s little room, he had the consoling surprise of finding a suffering beggar occupying the Professor’s bed. By what accident this needy one had obtained such a privilege was not known; the fact only remained that the poor creature was occupying the bed by direction of the Professor. Such example of tender charity inspired in the involuntary witness an ardent desire of imitating it.