What a Modern Catholic Believes About Women, by Sister Albertus Magnus McGrath (1972)

Posted in Books by Sinsinawa Dominicans

Later reprinted as The Church and Women, Sinsinawa Dominican and Rosary College history professor Sister Albertus Magnus McGrath’s What a Modern Catholic Believes About Women was one of the early Catholic feminist titles, and strongly influential on Sinsinawa Dominican radical feminists such as Sisters Kaye Ashe and Donna Quinn.

A more truly apt title might be What a Modernist Catholic Claims the Church Believes About Women. It is an impressively thorough and thoroughly tendentious and polemical history of Catholic thought about man and woman and the primacy or headship of man over women, with a view toward absolutely eradicating any such dynamic. The book’s out-of-print status is now probably permanent, given Sister Albertus Magnus’ prominent and unabashed exploitation of the n-word to equate the Church’s attitude toward women with bigotry and oppression against blacks. What a Modern Catholic Believes About Women culminates in a call for “women’s ordination” as necessary for justice.

What a Modern Catholic Believes About Women seems to owe a heavy unacknowledged debt to the 1968 book The Church and the Second Sex, by post-Catholic, post-Christian lesbian feminist “theologian” Mary Daly, who had been a teacher at the Rosary College study-abroad program in Fribourg, Switzerland and fellow doctoral student with Sinsinawa Dominicans like Sr. Kaye Ashe, while authoring that book.

A Chicago history source gives insight into how secular feminist politics in the couple of years leading up to the publication of this book undoubtedly contributed to the militancy of What a Modern Catholic Believes About Women: “McGrath was a member of the National Organization of Women and an ardent proponent of the Equal Rights Amendment; she went public with her endorsement of ERA in an advertisement in the Chicago Sun-Times that featured her photograph and quoted her as saying, ‘Sometimes I think Illinois seems almost past praying for when it comes to equality for women.'” It was in 1972, the year of publication of What a Modern Catholic Believes About Women, that the ERA was passed by Congress, though it was not subsequently ratified by enough states (Illinois was one of those who refused it), which was credited partly to Phyllis Schlafly, a Catholic who argued that there was a danger the ERA would be used to legally persecute the Catholic Church for not ordaining women.

One excellent thing about Sister Albertus Magnus is that she does love Jesus, and she shows us how loving He was toward women. However, she contrasts Saint Paul.

A key impact the work of Sister Albertus Magnus seems to have had on some of her sisters was via her teaching of “Paul’s denial that women are created in the image of God.” Whereas in Genesis 1 God creates man and woman both out of clay in His image and likeness, in the alternate creation narrative of Genesis 2 He creates Adam, puts him to sleep and takes out a rib, from which He fashions Eve as a fitting help to Adam (no mention being made of God’s image in this version). Saint Paul says, based on this, that man is in the image of God, and woman is like a reflection of that image, and he makes the point that woman was made for man and not vice versa. There is an ordered aspect of the relation of man and woman: the man is the head of the woman, an image of Christ as head of His bride the Church, for whom He sacrifices Himself. Sister Albertus Magnus quotes the Medieval canonist Gratian stating straightforwardly what she wants to scandalize us with: “woman was not made in God’s image.” On the other hand, she tells us Saint Paul””badly weakens his own argument by admitting: ‘However, though woman cannot do without man, neither can man do without woman, in the Lord; woman may come from man, but man is born of woman–both come from God.” Also, she tells us Saint Augustine and Saint Thomas Aquinas both held that both woman and man are in the image of God in the faculties of the soul of intellect, will and memory. Sister does not want us to long suspect that the equal dignity of man and woman (though toward the end of the book she quotes St Pius XII saying so) is the Catholic belief:

But woman is still second-rate in the Catholic view. While she shares the essential character, the possession of intellect and will, she is inferior (in an approved 1960 Catholic publication) in the accidental qualities, the natural and supernatural virtues which perfect the essential likeness. The intellectual virtues of reason and understanding, the cardinal virtues of prudence, justice, fortitude and temperance, the theological virtues of faith, hope and love are all found in higher degree in man (says this authority) because Paul says that “man is the head of the woman.”

Her source for this “information” about “the Catholic view” is not Saint Augustine nor Saint Thomas. It is not from some Papal Encyclical. It’s not Vatican II, Vatican I, or the Council of Trent. Rather, from it’s an 1884 Catholic dictionary that had gone through several rounds of revisions prior to the 1960 17th edition Sister referred to.

Until Saints Dominic and Francis of Assisi founded the first mendicant orders of friars to re-evangelize Europe in the 12th century, there existed no other form of religious life (ie vowed life in community founded on the evangelical counsels of poverty, chastity and obedience, and formally recognized by the Church) than monastic life, and for centuries more after that, the female Franciscan and Dominican religious, and all other women religious, remained monastic and contemplative, the praying heart of the Church. The men were the “first order,” the nuns the “second order,” and there was also a third order, aka brothers and sisters of penance, comprised of lay people; apostolic religious sisters arose not so much from the monastic nuns as from these and other lay movements which (though the road was rough) increasingly proved their worth, won popular and ecclesiastical acceptance, and eventually became classed as a new category of women’s religious life. But all that is how I myself describe it. The thrust of Sister Albertus Magnus’ version of the history of sisters focuses heavily on the idea that monasteries were basically a medieval “refuge for surplus females” upon which men imposed “minute restrictions” and “minute details about windows, walls, moats, hedges.”

What the official Church sought (with more or less consistency) as the ideal condition for religious women was that they should be neither seen nor heard…. [T]he motto dear to the hearts of the male clergy was always “aut maritus, aut murus” (“either a husband or a wall”).

In these past ages, it really was generally disadvantageous to be an unmarried laywoman (What a Modern Catholic Believes About Women points out the Industrial Revolution as a point when that particularly began to change), and some made immoral choices in the interest of supporting themselves. Sister Albertus Magnus asserts improbably that a particularly dismal observation about society constitutes “the Church position” on prostitutes:

With respect to prostitution, St. Thomas, following St. Augustine, states the Church position in this way: The prostitute is like “the sewer in a palace. Take away the sewer, and you fill the palace with pollution… take away prostitutes from the world, and you will fill it with sodomy. Wherefore Augustine says… that the earthly city has made the use of harlots a lawful immorality (licitam turpitudinem).”

Some updating to reflect a greater sensitivity and respect for women has been a blessing for everyone. It appears that “the use of the woman” used to seem unconcerning to male authors of theological texts for male readers, as a technical euphemism for sexual intercourse. The phraseology recognizes that this act requires the physically active participation of a man, while the woman’s receptive physical passivity after having given her consent would not necessarily be an obstacle to its fecund consummation. But “use of woman” strikes women readers obviously differently: “the wife as a mere instrument for the husband’s pleasure.” Sister Albertus Magnus, who far outstrips all the men in being full of insulting ideas about women, and is far more intentional about them, continually brutalizes us with more of her own “strawman” version of Christian doctrine:

The Christian era continued to honor woman as mother. Somewhat negatively, this honor was expressed in the view that woman required a double redemption: the one, universal, that she shared with man; the second, through the pangs of childbirth and the hardships of rearing children, redeemed her from the original sin of her femininity.

While the idea of men and women, husbands and wives, really loving one another is sadly not much a part of the book, Sister Albertus Magnus continually returns to a reductionistic view of woman as “an ambulatory incubator.” Her dripping scorn toward males chillingly overflows as apparent scorn toward the divine Paternity.

[T]he woman was merely a passive instrument furnishing in her womb “the good earth” in which the all-powerful seed could grow. Any woman would do for this anonymous function, so that the mother does not matter except as being sufficiently segregated to ensure legitimacy. One wonders if it is this view which requires that God as Creator be called Father.

As you might guess, Sister Albertus Magnus is also unhappy that “Methods of decision-making, particularly in matters vital to women such as the birth-control issue, serve only to alienate when they customarily ignore the wisdom, insights, and expertise which women possess.” Thus was ushered in an age of sexual corruption and perversion, wherein a great many women devalue and reject both the good of motherhood and the good of virginity–and, as Humanae Vitae warned, men have taken degrading advantage of the ever more ready availability of commitment-free, responsibility-free “use of woman.” Unfortunately, the hated term describes the reality in our brave new era of separating sex from parenthood, better than ever–men and women both use one another, often with no interest at all in Matrimony and family. Yet, from Sister Albertus Magnus’ perspective,

The sin of woman is too little pride, the retreat into the safe “little woman” role, and a toleration both of the sentimental twaddle which characterizes much of the traditional preachment about motherhood and virginity, and of the Church as over-protective of women on the one hand, and on the other, as the land of the perpetual put-down.

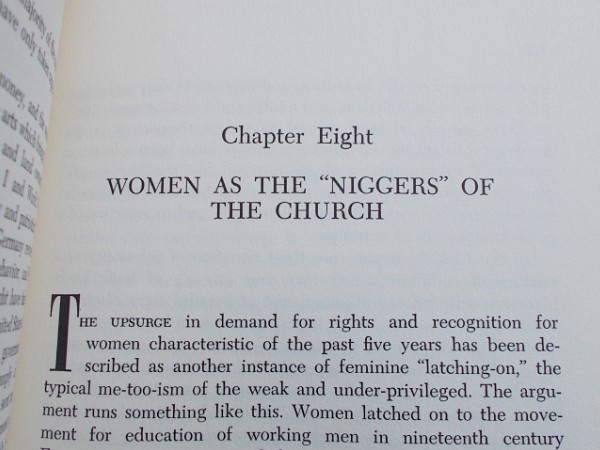

The last chapter is this, which I refuse to type:

“Especially, the influence of the Black Liberation Movement has been great.” Sister Albertus Magnus calls the phrasing in the above chapter title “an almost inescapable comparison.”

Not everything in this book is wrong. This chapter includes one outstandingly reasonable request: “It does not seem to much to ask that the Church repudiate the statements from the patristic age and after which see women as diminished and inferior beings.”

The Church and her leaders heard women’s voices about this. Blessed John Paul II in particular made a fresh, loving, and moving presentation of the Church’s view of women in his encyclical Mulieris Dignitatem, On the Nature and Dignity of Woman and his famous Letter to Women on the occasion of the UN Women’s Conference in Beijing (attended by some Sinsinawa Dominicans, though some people later questioned their participation at this famous family-planning-policy-setting occasion), as well as his famous series of audiences On Human Love in the Divine Plan, known as the Theology of the Body. A typical engaged, practicing Catholic young woman today has encountered this loving and wholly respectful contemporary presentation, is disillusioned with the sexual revolution and its ever more obvious harms, and has never met anyone who wants to argue that “woman is not made in God’s image.”

The denouement of What a Modern Catholic Thinks About Women, is a treatment of “one final question of the position of women in the contemporary Church which must be faced: the ordination of women to the priesthood.” In addressing objections, she points out that God in Himself is pure spirit, and “to attribute to Him male sexuality would be a theological error,” and while I am going to follow up by going deeper I think this is rightly said, though, “Jesus Christ on the other hand is undoubtedly male.”

Besides the fact that Jesus ordained men only in the Upper Room at the Last Supper, there is the fact that sacraments use specific signs, and for priestly ordination, a man is necessary. A woman is not an image of a husband or father; a woman is not an image of Christ as Bridegroom of the Church. I noticed something important that Sister Albertus Magnus does not acknowledge, either in the discussions of women as “ambulatory incubators” or in the discussion of whether maleness is a relevant and necessary attribute for a priest: the Holy Spirit is the Giver of Life. Granted, she is not a theologian. But we pray this in the Nicene Creed. She has wanted to demythologize “the all-powerful male seed” planted in the “earth” of the womb, and she points us to the scientific understanding that “two life powers, the chromosomes from both mother and father, neither of which has primacy over the other, unite in generation.” But her account, all too full of biological detail, neglects to mention that man and women are cooperators with God Who in a unique act of creation gives the soul of the tiny new person. This gift of life within the mother is an act of God, in cooperation with the parents. It is this new-created soul, united with the so-tiny and growing body in the “earth” of the womb, that is the life and the ultimate controlling principle of the new person. And when the child grows, is born, and then is baptized, the Holy Spirit gives the divine life, the higher and supernatural life, the life of Grace in the soul, and makes it a partaker in His own life. That is the immense capacity that the person has because she is made in the image of God in the faculties of her soul, intellect, will, and memory, capable of faith, hope, and charity. If the soul were not in the image of God it could not possess these virtues and be united with Him. It is not any distortion to call this loving giver, Our Father. It is a very tender name, and is a distortion to refuse to call Him that. It has to do with the nature of this relation of persons, not so much attributing to God “male sexuality” as such.

Sister Albertus Magnus does not necessarily even ask the right questions on the subject of “women priests,” which for instance include: “How, if women are, as future priests are apparently taught they are, like brute beasts in their sexual appetites, can they be held to any moral accountability?” and: “First, what makes the result of baptism different for women than for men?” She tells us that the Catholic Theological Society of America suggests in a report “that deacons (and deaconesses) might well be able to hear confessions and give absolution, as well as to administer the Sacrament of the Sick.” Um, no. What on earth is the matter with the Catholic Theological Society of America?

She feels that if there is to be any hope of them becoming priests, “Women must prove themselves in confidence and freedom in their lives in the Church and in all other aspects of their lives…. Women must work out on their own business and social life, in culture, politics, and marriage what the meaning of the Gospel message is in their complex human situation, without much expectation of, or help from authoritative voices which will comfort them that they are ‘right.'”

“The Church is not meant to be the Church of the hierarchy, the Church of men. It is the Church of Christ who loved and befriended and was served intimately by women.”

In this, Sister is at odds with Vatican II, because Lumen Gentium doesn’t want her to set these things in opposition:

[T]he society structured with hierarchical organs and the Mystical Body of Christ, are not to be considered as two realities, nor are the visible assembly and the spiritual community, nor the earthly Church and the Church enriched with heavenly things; rather they form one complex reality which coalesces from a divine and a human element. For this reason, by no weak analogy, it is compared to the mystery of the incarnate Word.

What a Modern Catholic Believes About Women is short and not too dense, and has a lot of interesting information though not enough supporting explanation, but it was a chore to read anyway, because it is tiresomely tendentious and negative. I longed for the author to approach her historical information in keeping with the mind of the Church. It is definitely the work of a historian rather than of a theologian, but I didn’t know when to trust the way she was using her out-of-context quotations–I did not trust her much at all, since the way she was presenting “the Church’s position” was so continuously unfair. In at least one case I looked something up in the Summa Theologiae and found that what she had quoted via another author wasn’t what it seemed, it was from one of the “objections.”

In the case of Saint Paul and the matter of headship, I dug into what he was saying and looked at notes in several Bibles, as well as other sources, to understand it and wound up really appreciating that she had drawn my attention to something that is usually glossed over. I was not offended by what Saint Paul was saying, especially since he elsewhere values mutuality, and since I saw it oriented above all to Christ as head of the Church, Matrimony having a high dignity as a holy image of that, and as a lay woman dedicated to Him in single-heartedness and chastity, I am very happy to acknowledge Jesus’ headship over me. How can someone be familiar with the Annunciation and the Beatitudes and “the last shall be first”, and think that any Christians, men or women, must fight any imputation of our own lowliness tooth and nail?

Please forgive me, I am moved to mention that the experience I have had as a Catholic which this book most kept calling to mind was actually an encounter with a Freedom From Religion Foundation counter-demonstrator at our Stand Up For Religious Freedom rally against the Obamacare contraceptive mandate. An angry-faced atheist woman fairly snarled at me, “The Catholic Church hates women!” I said, “I go to Mass every single day, I am extremely involved in the Church, and if that were true I would have noticed by now. The Catholic Church upholds and defends my dignity as a woman in a way that the secular world seems bound on destroying.”

–by Elizabeth Durack