On whether to give honor to Almighty God, Father, Son and Holy Spirit–Part 1: Dominican Praise

Glory be to the Father, and to the Son, and to the Holy Spirit, as it was in the beginning, is now, and will be forever. Amen. Alleluia.

This doxology begins each hour of the Liturgy of the Hours–words deeply familiar for most religious sisters and all priests.

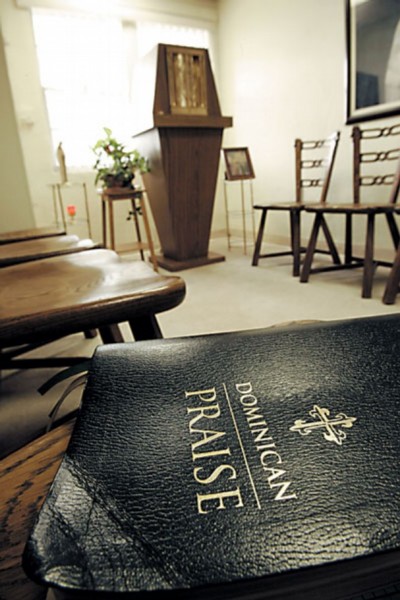

The most astounding and disturbing things I read on the Sinsinawa Dominicans’ email discussion list archive SinsinOP were the discussions about what language to use for the Divine Persons of the Trinity, instead of “Father, Son, and Holy Spirit.” Some speak of wanting a greater variety of words for God and flexibility; others are very radical and want to do away with all male language for God: “I no longer relate to God as father or ever use the word ‘he’ when speaking about God,” wrote Sister Patty Caraher in 2009. She’s not alone. Many Sinsinawa Dominican Sisters say they don’t want to renew their vows with the traditional formula that begins “To the honor of Almighty God, Father, Son, and Holy Spirit…”; when a vote was taken only a slight majority of 54% wanted no change. Some wish they could change their Constitutions to remove all male language for God–but know the Vatican would not go along with it. The Dominican Sisters’ Liturgy of the Hours-style prayerbook Dominican Praise uses a novel and genderless doxology: “Blessed be our saving God, Creator, Christ and Spirit, now and forever. Amen.” This is not simply neutral. There are obvious and grave theological problems with refusal to speak of God as Jesus’ Father, or refusal to speak of Jesus as a man.

Prayer and gender politics

Let us begin with liturgical prayer. In the June 1969 second issue of the Sinsinawa Dominican publication for congregational change, exCHANGE, Sister Julie Garner wrote an article on Contemplative Prayer in which she also voiced concerns about how the culture of the ’60s seemed to be affecting liturgy. Feminist language wasn’t yet the big thing, but she still felt the need to point out that they’d waited a long time for the privilege of praying the prayer of the Church (the Liturgy of the Hours aka the Divine Office–the Church’s official public prayer, together with the Mass), and she saw a danger that although that has finally been granted and encouraged by Vatican II, it would not not be appreciated by sisters, or the way of praying it tarnished by hippie culture.

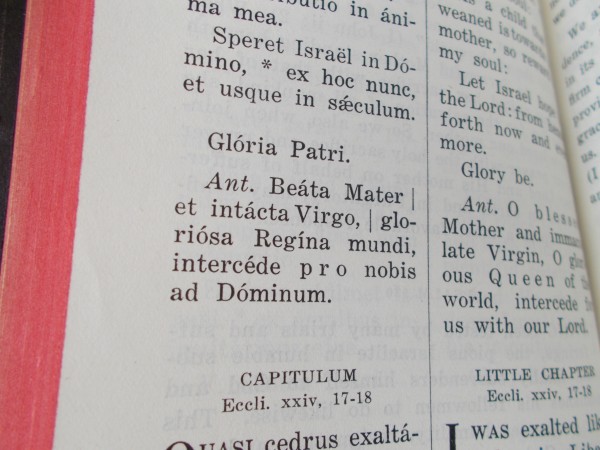

In the days before the Second Vatican Council, the Sisters prayed in Latin the Little Office of the Blessed Virgin, which the Catholic Encyclopedia describes as “A liturgical devotion to the Blessed Virgin, in imitation of, and in addition to, the Divine Office.” It was beautiful, and user-friendly for those who didn’t actually know Latin, but pretty much the same from day to day; the Divine Office on the other hand cycled through all 150 Psalms, and the whole schedule of liturgical feasts, and had a far greater significance in the life of the Church. The Little Office largely fell out of use after Vatican II newly allowed religious to pray the Divine Office in the vernacular (but take note that the Council also specifies: “The version, however, must be one that is approved.” –#101 par. 2, Vatican II Constitution on the Sacred Liturgy). In the words of a Sinsinawa Dominican in January, 2013, the “Divine Office connects us with the whole Church and its liturgical prayer.”

In the days before the Second Vatican Council, the Sisters prayed in Latin the Little Office of the Blessed Virgin, which the Catholic Encyclopedia describes as “A liturgical devotion to the Blessed Virgin, in imitation of, and in addition to, the Divine Office.” It was beautiful, and user-friendly for those who didn’t actually know Latin, but pretty much the same from day to day; the Divine Office on the other hand cycled through all 150 Psalms, and the whole schedule of liturgical feasts, and had a far greater significance in the life of the Church. The Little Office largely fell out of use after Vatican II newly allowed religious to pray the Divine Office in the vernacular (but take note that the Council also specifies: “The version, however, must be one that is approved.” –#101 par. 2, Vatican II Constitution on the Sacred Liturgy). In the words of a Sinsinawa Dominican in January, 2013, the “Divine Office connects us with the whole Church and its liturgical prayer.”

A snapshot of the end of a psalm, from the Little Office of the Blessed Virgin, in the Office Book for Dominican Sisters, copyright 1941 by the Dominican Sisters of Racine, Wisconsin

Father Cyril Wahle, OP wrote in the introduction to the old Office Book for Dominican Sisters: “The purpose of our prayer is first, the glory of God whose incomprehensible perfections we exalt whenever we say: ‘Glory be to the Father, and to the Son, and to the Holy Ghost’.” This doxology has been in use since the fourth century, and had to be defended at that time because the Arian heretics wanted to make the Son less than the Father, as one can find out all about by reading Saint Basil the Great.

In our own day, the error that militates against this prayer, is that motivated by a “liberationist” feminism, that says that “Father”, “Son” or any other masculine terms are not truly eminently fitting terms for God, but are limiting and come out of a particular culture, and should be eradicated. This was part of the liberationist (marxist) feminist program of changing meanings and practices in the Church to “correct” what was perceived or claimed to be marginalization and oppression of women.

Sister Ann Marie Mongoven wrote on the Sinsinawa Dominican email discussion list SinsinOP in February of 2002, and her perspective is typical of many Sinsinawa Dominicans:

We can no longer burden our imaginations with a deadly literalist understanding of God language. Vatican Council II released us from that burden. I agree with Elizabeth Johnson and Catherine LaCugna that the use of “Father” and “Son” presents a difficulty from a feminist perspective. And I am grateful to [those who are] urging us to find language that expresses “the ancient mystery of the Trinity.” That is not only our work as Dominican women but as women in the Church. The whole Church needs to and is finding new metaphors and images to add to the Tradition. LaCugna says that “the insights of trinitarian theology should free our imaginations without forcing us to abandon our tradition.” But we need to realize that no metaphor, neither Father, Son, nor Holy Spirit can be understood in a literalist way.

If Mary is the mother of Jesus, and it is a non-literal metaphor that God is Jesus’ Father, who do they imagine is Jesus’ other parent?

Dominican Praise, a Scripture-mangling substitute for the Divine Office

In the late 90s, Sisters from 18 different Dominican congregations began to work to bring about “the creation of a Dominican Women’s Prayer Book that incorporated the Liturgy of the Hours and specific Dominican emphases. Since the license for ICEL is frozen, we formed committees and have been working assiduously.” ICEL is the International Committee on English in the Liturgy, the body that holds the copyright for Catholic liturgical texts (such as the Liturgy of the Hours) in English translation, and licenses them to publishers. These ecclesiastically approved liturgical texts cannot be altered, which may be what is meant by saying “the license for ICEL is frozen”.

I was very surprised to find that, while other religious orders (for instance the Discalced Carmelites and Franciscans) diligently translated from Latin the “proper” offices for the Saints of their orders, obtained ecclesiastical approval of the English versions, and published them in book form as a supplement to the Liturgy of the Hours, the Dominicans did not. Father Augustine Thompson, OP, a professor in California knowledgeable about Dominican liturgy, told me in response to an email inquiry: “There are two English versions of the Dominican propers. That done by the Central Province many years ago for experimental use. It was never submitted for approval. I don’t know why, perhaps because it was ‘experimental.’ It does not use degendered language. There is a version done by the Eastern Province more recently, and I have been told it has been approved by Rome, but I have not seen it.”

Fr Thompson told me he had never heard of Dominican Praise. In response to my question as to whether it could fulfill a priest’s obligation to pray the Liturgy of the Hours, he said “The only books that fulfill a priest’s obligation to the office are the editio typica [ie, the Latin text of the Liturgy of the Hours] or an approved translation.”

Although it follows a similar pattern, Dominican Praise is not a translation of the Liturgy of the Hours, but “a provisional book of prayer for Dominican women.” It is part of the phenomenon that past Sinsinawa Dominican Prioress General Sister Kaye Ashe described approvingly in her book The Feminization of the Church?: after the Church declined to approve “inclusive language” texts for the Mass and the Divine Office, some people began to “turn to feminist or women’s liturgies either to supplement or replace them.” Dominican Praise’s prayers feature “inclusive language and broader naming of God.” It gives two novel doxologies that could be used instead of “Father, Son, and Holy Spirit,” and advises choosing one and using it throughout the prayer, these include “Blessed be our saving God, Creator, Christ, and Spirit, now and forever. Amen” and one referring to “…Creator, Redeemer, and Holy Spirit….” Dominican Praise uses entirely new, feminist translations of Scripture readings and psalms, from the original Hebrew and Greek. Sinsinawa Dominican Sister Mary Margaret Pazdan was one of the translators of the Greek New Testament readings and canticles. Even the Magnificat, Mary’s song of exultation after the conception of His Son in her womb, excruciatingly avoids any reference to God as “Lord” or by masculine pronouns:

My being proclaims the greatness of God;

my spirit rejoices in God my Savoir,Who has looked lovingly on me in my affliction.

From this day all generations will call me blessed.For God, wonderful in power,

has done great things for me.Holy, God’s name!

Whose mercy from generation to generation

is to those who stand in awe….

The book includes some non-scriptural “alternative readings” for Morning or Evening prayer, which include several by Dominican Sister Mary Catherine Hilkert, I think a couple from Vatican II documents, one from the 1986 USCCB document “Economic Justice for All,” and even one by controversial feminist/panentheist theologian Sister Elizabeth Johnson.

Sister Kaye Ashe’s 1997 The Feminization of the Church?, written about the time the Dominican Praise project was getting started, refers to to “Numerous committees and commissions” at work on “inclusive language translations of the Bible, lectionaries, hymns and prayer books,” whose “brave efforts have not been spared caustic criticism,” as she illustrates by quoting James J. Kilpatrick writing in the Washington Post: “vandalism of this magnitude ought not to go unremarked.” The Sinsinawa Dominicans ordered a total of 391 copies of Dominican Praise, of the total 2005 edition of almost 5,000 copies, published by Liturgy Training Publications (LTP).

In 2007, interest in a second printing didn’t meet the minimum order threshhold of 3,000 copies, leading to shortages of the book. The Liturgy of the Hours was not necessarily what they prayed with instead, but rather, both before the availability of Dominican Praise and after, they preferred another unofficial, feminist-language alternative: “If anyone has a copy of Dominican Praise she is not using, will you please send it to me. I lost mine somewhere between Wisconsin and Florida. Sister Kathleen and I have been forced to use the People’s Companion to the Breviary put out by the Carmelites who never heard of a Dominican saint.” The Trinitarian formula in that book is: “Source of All Being, Eternal Word, and Holy Spirit.”

Heroine of orthodoxy Sister Francis Assisi Loughery‘s 2003 obituary noted that “Praying the daily office, Francis prayed aloud to the Saints for all who are in need of our prayers.” But I believe it is a rare one who is praying the Liturgy of the Hours anymore. It is not believable that the sisters are devotees of Vatican II; not only in this, but in so many things, they seem to care little what it really says. From the Constitution on the Sacred Liturgy:

The competent superior has the power to grant the use of the vernacular in the celebration of the divine office, even in choir, to nuns and to members of institutes dedicated to acquiring perfection, both men who are not clerics and women. The version, however, must be one that is approved.

Continue reading Part 2 of this article, on the sisters’ vow formula ->