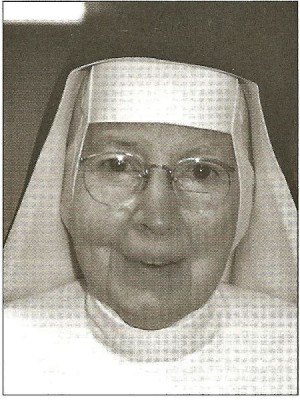

Sister Francis Assisi Loughery, who spoke up for Catholic beliefs

Ann Therese Loughery was born July 26, 1922 in Cicero, IL, to Cornelius Francis and Mary (Ryan) Loughery. She had two brothers, Gerald and Francis, and a sister, Dorothy. She received Catholic schooling at Mary, Queen of Heaven Grade School in Cicero and Saint Patrick High School in Chicago, then a bachelor’s degree from Chicago’s DePaul University, in philsophy and English, after which she taught for a little while at St Patrick High School.

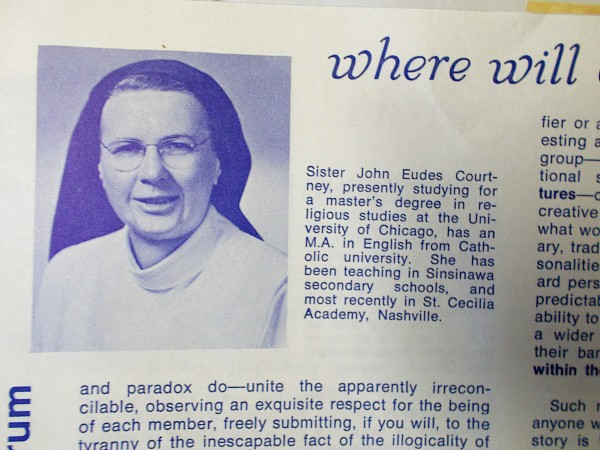

She discerned a call to the Dominican Sisters of the Congregation of the Most Holy Rosary of Sinsinawa in her late 20s, entering the novitiate a year after a friend from DePaul, Mary Courtney, who became in religion Sister John Eudes. Ann was given the name Sister Francis Assisi. Some new friends for life would be made in the novitiate, particularly Sister Angela Donovan, who would serve as prioress at the two convents where Sister Francis would spend her last years. They made their first vows in 1950. During this period of temporary vows the solid course of studies appears to have included the New Testament, the Rule of Saint Augustine and the Constitutions of the order, Gospel of Jesus Christ by Joseph Lagrange, OP, Fr Reginald Garrigou-Lagrange OP’s The Three Ages of the Interior Life which was then very newly translated into English by a Sinsinawa Dominican Sister, Religious Vows and Virtues by Blessed Humbert of Romans, and the “Treatise on Obedience” from the Dialogues of Saint Catherine of Siena. Their final profession was in 1953.

Also in the 1953 profession class was Keverne (Kathleen, or Kaye) Ashe. These intelligent women would again spend a formative period of their lives together as they pursued advanced degrees at the Catholic University in Fribourg, Switzerland. A storm of culture change was brewing, and in the whirlwind of the 60s and 70s Sister Francis Assisi, a prayerful woman profoundly devoted to the Eucharist, would hold fast to the Faith as it is proclaimed by the Church, while Sister Kaye’s views would evolve toward the most radical feminism and antagonism toward “the institutional church.” Kaye would become the congregation’s Prioress General in 1986–while Sister Francis Assisi was doing her best to incarnate a more traditional way of religious life. Many others, both the radical sort and the traditional sort, would leave the community, but they remained. When Sister Francis Assisi passed away in 2003, Sister Kaye, writing on SinsinOP, remembered “her witticisms when we were postulants and novices, her authentic holiness, her principled fidelity to her convictions about our shared religious commitment.”

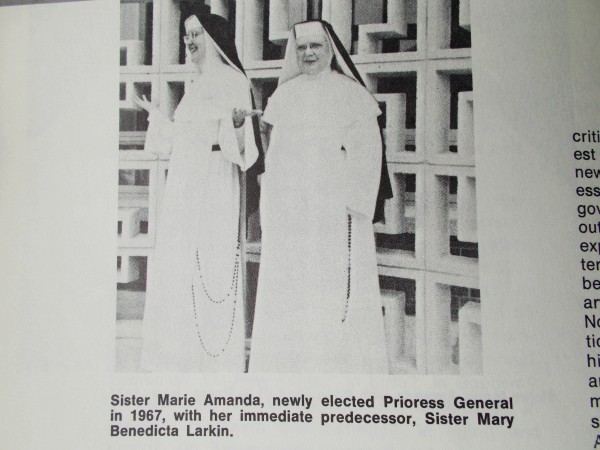

After Profession, Sister Francis Assisi taught Latin and English for five years at the congregation’s Bethlehem Academy in Fairbault, MN. Mother Mary Benedicta Larkin was elected prioress in 1955, and at the time no one suspected she would be the last to be called Mother Superior. Mother Benedicta must have been aware of Sister Francis Assisi’s good qualities, since soon after her 1955 election Sr. Francis was made mistress of novices and of postulants, from 1956-1958. One of her postulants recalled her dry wit:

She was a spiritual lady with a wonderful sense of humor as some have already mentioned. My favorite memory, when we were postulants in 1957: Saturday afternoon we assembled to study as we took showers and baths to get ready for Sunday. This particular Saturday we were studying in silence and Sr. Francis was at her desk reading. We heard footsteps from the third floor approacing with great speed to the doorway of the postulant’s room. As I recall it was […] who said breathlessly, “Sister, there’s a bat in my tub.” We began to giggle and Sr. Francis looked up and calmly said, “What’s the matter, Sister, didn’t he sign up?” That was the end of studying. For those who do not know, we had to sign up for a time as there were so many of us. Sr Francis had a gentle and loving way with all of us.

And the very sister said to have startled the bathing bat wrote:

I remember Sister Francis Assisi with great fondness. Even though she seemed a little too heavenly for me when I was a postulant, I grew to love and respect her deeply. She was not afaid to speak her truth in spite of what others thought .Her life will always challenged me to search for the truth and live it.

Villa des Fougères today. The Rosary College study abroad program was last held there in 1977-78. The building is now occupied by the “Ecole-Club Migros”. There is still an American study-abroad program in Fribourg that seems to be secular but sees itself as a kind of heir to the Rosary College program.

After this service, Francis Assisi was sent to the Sinsinawa Dominicans’ Villa des Fougères in Fribourg, Switzerland, the residence for the Rosary College study-abroad program, to attend the University in that city. It was a rich cultural as well as academic experience, and there was the opportunity to travel to see other parts of Europe. The Second Vatican Council met from 1962-1965. Fribourg seems to have been at that time a place where the university had a conservative reputation, but where theological trajectories issuing out of various disturbed cultural and historical contexts were developing in quite opposite directions.

Two of Rosary-in-Fribourg’s teachers of this era illustrate this vividly. Prior to rising to fame and great influence as a post-Christian radical feminist lesbian theologian, Mary Daly taught philosophy and/or theology at the Sinsinawa Dominicans’ Ecole de Hautes Etudes at Villa des Fougères, from 1959-1966. Sister Kaye Ashe, director and superior of the house from 1961-1968, had already been influenced while a student at Rosary College in Chicago, by a fellow Sinsinawa Dominican on the leading edge of the feminist movement, Sr Albertus Magnus McGrath (see also my review of Sister Albertus Magnus’ 1972 radical feminist book What a Modern Catholic Believes about Women, which appears to have drawn significant inspiration from Daly). Mary Daly’s thoughts resonated with Kaye. She reports that she told an audience of priests in Berkeley in 2006,

[I]n Fribourg, Switzerland, where I got my doctorate I met Mary Daly, who was earning a doctorate in theology and philosophy, and working on her first book [ed.: published in 1968] “The Church and the Second Sex.” Even if we had a semester instead of a morning together it would be impossible to describe the kind of mind-blowing, transforming effect those books and scores of others since have had on the way I and millions of other women and men look at gender relations, at marriage, at the institution of the church, at history, politics, law, theology, ethics, friendship, scripture, the sacraments, the meaning of power and authority…in short everything that is of importance to us.

Daley thanked Kaye Ashe on the acknowledgements page of her most famous book Beyond God the Father, published in 1973, and Kaye mentions Daley prominently in her own book The Feminization of the Church?. They were still in contact in the 1980s before eventually the friendship broke off; Daley was not an easy personality: “She both thrilled and threatened me — thrilled me with the depth of her intelligence and the courage of her convictions, threatened me as a woman religious who intended to stay in the Church while she chose to leave it. ”

Another instructor with a very different theological orientation was Bernard Faÿ, a complex and controversial figure who Wikipedia says (based on a French language source?), taught French literature at Rosary-in-Fribourg during the 60s, though I cannot be entirely certain since this is not actually mentioned by any Sinsinawa sources that I can find,–perhaps for obvious reasons however. A Harvard-educated royalist French Catholic said to be an anti-Semite and said to be “gay,” he had protected American Jewish lesbian authors Germaine Grier and Alice B. Toklas from the Nazis. After the war was convicted of collaboration with the Nazi-cooperator Vichy regime (he was the head of the French National Library at this time, and was the Vichy government’s anti-freemasonry director whose cooperation is said to have led to many freemasons’ deportation to death camps) and imprisoned, then escaped, partly with financial help from Toklas, and fled to Switzerland. The outcome of Vatican II was especially disturbing for French Catholics of Faÿ’s sensibilities, and he wound up being one of a small group that caused Fribourg to become the place of the founding of the Society of Saint Pius X, among the others were such sound Catholics as Fr Marie-Dominique Philippe who became founder of the excellent religious order the Community of St John, and Cistercian Abbot Berhard Kohl. Initially that Society had permission of the local bishop to continue traditional formation of seminarians, but within a few years it sadly parted from the unity of the Church. The biography of the SSPX founder, then-recently-retired Master General of the Holy Ghost Fathers, Archbishop Marcel Lefebvre, records this, only short months after the approval of the Novus Ordo Missae:

It was then on June 4, 1969 when Professor Bernard Fay, Father Marie-Dominque, O.P., Dom Bernard Kaul, Father d’Hauterive and Professor Jean-Francois Braillard met with Archbishop Lefebvre on the dilemma. They took the aging prelate “by the scruff of the neck” and insisted “something must be done for these seminarians!” The “something” they had in mind was that Archbishop Lefebvre establish a seminary.

Strange but true: figures who would spark the most radical anti-Catholic feminism, and ultra-traditionalism, were teaching at the Sinsinawa Dominicans’ villa in Fribourg in the turbulent ’60s, with perhaps the effect of mutual scandal. At the same time, Rosary-in-Fribourg was not without fun; Kaye Ashe remembered fondly after Francis’ passing in 2003 “years spent in Fribourg together, and her spirited participation in the games and treasure hunts we devised to entertain ourselves.” In this milieu, Sister Francis Assisi earned a Bachelor of Sacred Theology degree from the University of Fribourg in 1961, and a Licentiate (like a Master’s degree) in the same field in 1963.

Meanwhile, an era ended, with the election at the 1967 General Chapter of a change-oriented new prioress and the ushering in of a period of experimentation meant to discern how to appropriately make changes called for by Vatican II, to culminate in new Constitutions submitted to the Holy See’s Congregation for Religious in 1977, which were approved in 1980. 1967 photo appeared in ExHANGE, Summer 1977.

In 1966 or 67 Sister Francis Assisi returned to Wisconsin to work on her thesis at Sinsinawa Mound where Mother Benedicta’s grand project of the new round chapel and auditorium complex and the huge new dormitories were freshly completed (in the optimism of 1960 the plans were drawn with rooms for 300 novices, though by the time of the project’s completion in 1966 the actual number of novices had plunged from 150 annually to several dozen. As of this writing, there is only one novice, who studies with novices from other Dominican congregations at a collaborative novitiate in Saint Louis.). Sister Francis then taught theology and Scripture at Madison’s Edgewood College in 1968-69, before moving back to the Sinsinawa motherhouse where she taught sacramental theology from 1970-1972. Sinsinawa Mound had just experienced, in 1969, the end of a long era with the closing of the Saint Clara Academy girls’ boarding school, the school that had originally been founded by Father Samuel Mazzuchelli in Benton, WI–to the great distress of some sisters and alumnae. A coed day school, Sinsinawa Mound High School, continued to operate for a time.

According to the Mazzuchelli Guild Bulletin of Winter 1970-71, Sister Francis Assisi was also the Sinsinawa Mound Archivist starting in 1970, and gave talks to lay groups such as the Catholic Daughters of America and the Mazzuchelli Assembly of the Knights of Columbus, the organization which subsequently undertook the effortful, costly, and wonderful work of fully restoring Father Mazzuchelli’s Saint Augustine Church in New Diggings. They now maintain this precious and unique church, still very similar to how it was in pioneer times, as a museum.

Sister Francis’ thesis was under the direction of the great Irish Dominican sacramental theologian Father Colman E. O’Neill. This wasn’t solely about books and fine Thomistic argument. Sister Angela Donovan, who seems to have been a close friend of her last years, said at her wake: “Francis spent hours in the presence of the Blessed Sacrament. Her love of the Eucharist was not only a spiritual exercise but the cause and completion of her doctoral work.” Her thesis was titled “The Eucharist, the End of All the Sacraments According to Saint Thomas and His Contemporaries,” and earned for her in 1971 a Doctorate of Sacred Theology from the University of Fribourg. This qualified her to become a member of the Catholic Theological Society of America, into which she was inducted the same year.

One source insists that none of the Congregation’s colleges ever would hire Sister Francis Assisi Loughery to a teaching position; I am not clear on why this was said, except that Sister Francis’ orthodoxy seemed to have some relevance. The information that she briefly was at Edgewood College is from the congregation’s official obituary, however it’s perfectly true she never was employed at any of the Sinsinawa colleges after that.

She engaged in some kind of further study at Union Theological School in Chicago. In 1972 she participated as a member of the Provincial Chapter for the Northwest Province, then the following year was an alternate delegate on behalf of her province, at the 1973 General Chapter. In the October, 1972 issue of ExCHANGE magazine, participants in the four Provincial Chapters that had recently met, gave their impressions of the chapter meeting. Sister Francis concernedly made note of one of the most serious shifts she was observing, the redefining of religious “obedience” according to democratic principles, such that now many sisters understood obedience to be owed to the decisions of the group, not really to a superior who would consult with subjects but still exercise personal authority in a sacred way. This seems to have created increasing difficulties as they struggled to edit their Constitutions in a way that could both enable them to live in accord with their altered understanding of the matter, and still gain approval of this essential text by the Congregation for Religious which necessarily upholds the Church’s view. Sister Francis Assisi quoted the Second Vatican Council document Perfectae Caritatis to show that is indeed still the Church’s understanding of religious obedience.

Through the profession of obedience, religious offer to God a total dedication of their own wills as a sacrifice of themselves; they thereby unite themselves with greater steadfastness and security to the saving will of God. In this way they follow the pattern of Jesus Christ, who came to do the Father’s will… Under the influence of the Holy Spirit, religious submit themselves to their superiors, whom faith presents as God’s representatives, and through whom they are guided into the service of all their brothers in Christ. (PC, #14)

Sister Francis Assisi Loughery writes in the October 1972 edition of the Sinsinawa Dominicans’ ExCHANGE magazine.

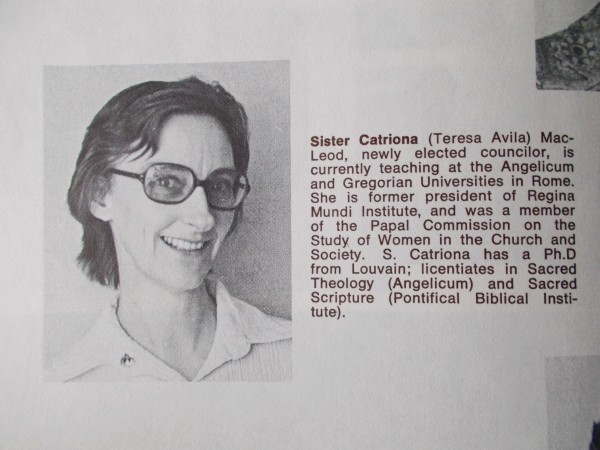

Sr Francis was invited in the same year to teach theology at Regina Mundi, the college in Rome for sisters and lay women, which she did from 1973-1978. Regina Mundi was probably not a bed of roses either; the president at the time was Scottish-born Sinsinawa Dominican Sister Teresa Avila MacLeod (who later went by the name Catriona), a past Rosary College professor whom a 1973 UK Catholic Herald article indicates intended to include discussion of “women’s ordination” on the agenda of a Commission on Women and Society to which she had been appointed by Pope Paul VI, regardless of the fact a memorandum had been sent emphasizing that this topic must be excluded. The Fall, 1975 issue of Sinsinawa’s ExCHANGE magazine includes an extensive interview with her, particularly regarding her controversial statements to the press as a member of this Women’s Commission:

In an interview published in the Fall, 1975 issue of the Sinsinawa Dominicans’ community-change-oriented magazine, ExCHANGE, Sister Teresa Avila (Catriona) MacLeod discusses Pope Paul VI and the Commission on Women to which he appointed her.

An ExCHANGE profile of Sr. Teresa Avila (Catriona) McLeod immediately after her 1977 election to the Provincial Council.

Besides teaching at Regina Mundi, one may speculate that Sister Francis Assisi may again have been studying in Rome. Although no other sources mention it, one person states that Sister Francis Assisi was among the first women students of the Angelicum, the great University of Saint Thomas. This is a plausible reason for her to want to be in Rome. It is not clear however.

In 1979 she accepted a position as a research assistant with the Leonine Commission in Washington, DC. This effort was established in 1880 after Pope Leo XIII asked the Dominican Order to create a Latin critical edition of all the works of Saint Thomas Aquinas, based on the best surviving manuscripts. They’d been laboring at this immense, important, and to most people obscure, task for 100 years. Sister Francis Assisi was the only sister to work in the American section of the Leonine Commission.

During the same time, Sister Francis Assisi’s old college friend Sister John Eudes Courtney had gotten involved in some of the country’s most noteworthy efforts of truly faithful Catholic education. Her experience and thoughts give a small glimpse into the type of concerns some sisters had about how the post Vatican II “renewal” was going.

The state of Catholic education in 1971, as seen in Sinsinawa ExCHANGE Magazine: Rabbi Monford Harris, who taught for four years at the Sinsinawa-sponsored Rosary College in Chicago (now Dominican University), wrote a very striking and spot-on article for ExCHANGE in which he sounded the alarm that the sisters were not actually giving students a knowledge of Catholicism, and that as a result students were rebelling against a Faith they knew very little about. This was accompanied by response articles by a priest and a sister–who both argued that handing on knowledge of the Catholic tradition was not what was most needed. “I felt vaguely uneasy reading Rabbi Harris’ plea for a teaching of tradition. Not because of opposition to the idea, but because I sense that tradition has a much larger place in Jewish faith and culture than in Christianity,” wrote Father Steve Shimek, who later left the priesthood and has participated avidly in activist dissent organizations such as Voice of the Faithful. Shimek’s feeling is that “[t]radition can be leaden, a drag.” Sister Melita Conlon’s response states that “[p]reviously our teaching of religion was factual, weighted with doctrine and dogma,” but the present era calls for “an experiential and existential rather than… the purely intellectual approach of the past.”

After her studies in Chicago, Sister John Eudes got on board with an exciting new, faithfully Catholic college in Virginia, which would begin classes in the fall of 1977. She became Christendom College’s first librarian, setting up 4,000 volumes on its shelves. History also records she was a participant in the school’s first ping-pong tournament. But the most famous fun fact about Sister John Eudes is that an old college friend wrote a a 1962 autobiographical novel Life With Mother Superior in which the author’s best Catholic boarding school friend “Mary Clancey” is based on her, and their hilarious, troublemaking escapades (actually, when she and the author were college age). This became a play and then a 1966 Hollywood comedy film with a lot of good Catholic “nostalgia,” The Trouble With Angels. Sister John Eudes’ schoolgirl character is played by Hayley Mills.

Getting to know about these sisters a little made me ponder why a few held fast to the Catholic Faith that had been handed on, while many others embraced incompatible deviations. I think Sister Francis Assisi’s devotion to the Eucharist was clearly one factor for her. It seemed to me that some lively and original minds, even “troublemakers,” were the ones who held fast to orthodoxy–while many more conventional ones went along with the crowd, excitedly conforming to the trendy spirit of the times.

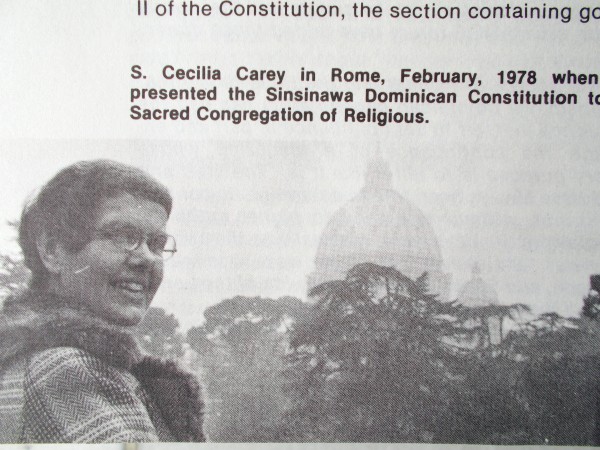

The late 1960s and 1970s had seen a period of freewheeling experimentation (ExCHANGE was the journal of that process), intended to sort out how to adapt to the new directives in the Second Vatican Council, but actually going far beyond that. This process culminated in the 1977 submission to Rome of the new Constitutions. In 1979, the Sinsinawa Dominican Congregation, then headed by Prioress General Sister Cecilia Carey, heard back from Rome that these all-new Constitutions, describing a significantly new and different way of life, had been approved, with only minor changes. The beginning of the letter from the Sacred Congregation for Religious is quoted thus in the congregation history Let Us Set Out; Sinsinawa Dominicans 1949-1985, by Sister Alice O’Rourke, OP.

These documents are not so much revisions of interim Constitutions previously submitted, but entirely new documents based on the experience of the Sinsinawa Community during the past ten years. They show, however, a careful consideration of the spirit and aim of the founder, Father Samuel Mazzuchelli, and of the directives of Vatican II, which are incorporated into the redaction. Certain amendments need to be made, but the texts, in general, are good.

This history also records that “since the work on the experimental constitution began in 1966, a few sisters had resisted the idea of completely rewriting the constitution,” wanting a continuity with the 1893 constitution that had been updated as necessary through the years. Sister Julius Loosbrock and Sister Magdalita McGinty made proposals to prioress Sister Cecilia in 1977, about what they believed to be essential features of apostolic religious community life. They also requested but were denied a means to bring their ideas to the whole congregation. The General Council wasn’t open to the proposals unless they were reconciled with the completely new constitutions that had been approved at the General Chapter (but not yet presented in Rome), but these sisters weren’t open to these new constitutions. While I have no detailed account of their ideas, one may reasonably surmise the way of thinking of these sisters was more similar to what was at that time called the Consortium Perfectae Caritatis, and later became the “other” Superiors’ group the Council of Major Superiors of Women Religious, which included groups of sisters that didn’t go along with with the Leadership Conference of Women Religious‘ defiance of Catholic beliefs and directives.

In April of 1980, after the definitive approval of the constitutions, a small group of sisters privately sent a letter to Pope John Paul II with requests for special provisions that would carve out a possibility to live their more traditional vision of religious life without leaving the Sinsinawa Dominicans. They wanted their own autonomous province, and privileges to include:

1) that of being governed by the Consitutions approved by the Holy See before 1967, duly adjusted according to Ecclesiae Sanctae [a document that included instructions on how to implement the Vatican II document on appropriate renewal of religious life, Perfectae Caritatis], the adjustments to be presented to the Holy See for approval. 2) that of submitting directly to the Holy See, through a provincial chapter, the names of those to be appointed by the S. Congregation to the offices of Provincial and Provincial Councillors; 3) that of receiving candidates, training them and admitting them to profession; 4) that of having an equitable arrangement with the Congregation for necessary financial aid.

When Sister Cecilia, the prioress, became aware of this via a June 25, 1980 letter from Archbishop Augustine Mayer of the Sacred Congregation for Religious, who was seemingly well disposed toward the request, she was determined in opposition and set about right away trying to find out who was involved and trying to persuade Archbishop Mayer not to go along with it, because it was not in keeping with the new constitutions. “She assured him that there would be no possibility of a financial arrangement.” But he wrote back saying that he had both the power and the will to grant the petitioners suspension of whatever in the constitutions conflicted, and that they would have their own provincial statutes, which would be termed a directory.

Sister Francis Assisi Loughery, picture accompanying her Spring, 1981 ExCHANGE magazine article titled “Examining Our Place in the Schools”

In the Spring of 1981, ExCHANGE, the editors of which would not have known at the time that she was part of the group that had petitioned the Holy See, published an article by Sister Francis Assisi. It was titled “Reexamining Our Place in the Schools.” She quotes a message of Pope John Paul II to the National Catholic Education Association in 1979: “Yes, the Catholic School must remain a privileged means of Catholic Education in America. As an instrument of the apostolate it is worthy of the greatest sacrifices.” She quotes also from an address of his to women religious exhorting their continuation in this ministry, in which he says women religious have made “an incomparable contribution.” Sister Francis says, “Unquestionably, the Holy Father is asking religious to persevere in their teaching ministry…. Why then are we withdrawing from the schools, precisely when the Holy Father is asking us to continue?” She analyzes the reasons very astutely, and points out some of the new ministries, such as the increasing importance of Directors of Religious Education and CCD teachers, have arisen as important needs precisely because of the withdrawal of sisters from the Catholic schools and the consequent “weakening of the parochial school system.” She also mentions a broadening of the concept of education to include other kinds of minstries. This was interesting to me partly because when I cited their charism as Catholic education to one Sinsinawa Dominican at the Mound in January, she looked honestly startled as if she hadn’t thought of it as that in a while.

In freeing our sisters for these various ministries, have we not weakened, have we not fragmented, our original charism? Does it make sense to protest we are dedicated to our Catholic schools, and then in the next breath add: the sisters are free to engage in diverse ministries?

Then Sister Francis Assisi quotes the 1979 LCWR president Theresa Kane, who is associated in every sister’s mind with her very famous public call that year in Pope John Paul II’s presence, that the Church “must” respond to the “intense suffering and pain” of American women “by providing the possibility of women being included in all ministries of our Church,” ie ordaining women. What Sr Francis Assisi quotes is Sr Theresa Kane calling for “redistribution of woman-power if we are to be in solidarity with the poor” which “may even lead many to step outside of the established systems, to eventually withdraw from established ministries such as Catholic schools and health ministries.” Sr Francis is very clear that she does not agree with this at all (and by reasonable inference does not agree with St Theresa Kane more generally)–and what she has to say may also reflect how she saw the key purpose of the proposal to the Holy See for a province with special privileges:

The challenge for Sinsinawa Dominicans in the 80s is clear: we must commit ourselves wholeheartedly once again to the ministry of the Catholic school; we must establish again beyond doubt our reputation as Catholic educators; we must assume leadership reawakening the Catholic religious of our country to this privileged role of the Catholic school in the building of the Church in the United States.

It is an issue that calls for prayerful reflection, honest dialogue, courageous action. Ultimately it is an issue that calls for an unambiguous response to the more basic question: Do we owe any special allegiance to the Holy Father? Is his voice merely one among many?

“It was not until April, 1981 that the names of all nine of the original petitioners were known [ie, to Sister Cecilia and the General Council], one of whom by that time had decided not to participate,” writes Sr. Alice O’Rourke in Let Us Set Out. The eight were: Sisters Julius Loosbrock, Magdalita Ginty, Clarentia Kelly, Gemella McLaughlin, Mary Emily Power, Mary Rose Powers, Francis Assisi Loughery, and Mother Benedicta Larkin.

Sister Cecilia and First Councilor Sister Ann Willits met with Archbishop Mayer in Rome about the matter in May 13, 1981. She had a counter proposal of a convent under the ordinary authority of the Prioress General, with what she termed a “monastic life-style.” This re-framing of the traditional way of life of active Sisters had negative connotations and also would have implied they were at odds with the intentions of the founder, Father Mazzuchelli, who wrote, in his commentary on the Sisters’ Rule, of a monastic way of life as unsuitable for the Dominican Sisters–by which he meant that extreme fasting, totally enclosed cloister, and praying all day and in the watches of the night rather than service and teaching, wasn’t for them.

On May 25, at the Archbishop’s suggestion, Sisters Cecilia and Ann met again with Archbishop Mayer, with Sister Julius Loosbrock and Sister Maria Michele Armato present also; the latter was another supporter of the plan, who had been one of the translators of the new 1967 translation of Father Mazzuchelli’s Memoirs published by Priory Press, and from 1967-1985 director of the congregation’s fine arts college at Villa Schifanoia, Florence, Italy. Sister Maria Michele Armato subsequently left the Sinsinawa Dominicans and founded a new Dominican community in Flemington, New Jersey, the Dominican Sisters of Divine Providence, which is a member of the more traditional Council of Major Superiors of Women Religious rather than the LCWR. According to the page on the CMSWR site, “Their main purpose as religious is to be deeply immersed in God through a serious prayer life. The specific work of the community is the spreading of the Kingdom of God through the apostolate of teaching.”

From the meetings there resulted an agreement approved by Archbishop Mayer, that the petitioners would be allowed to found a convent as a five year experiment, and that it would be under the authority of the prioress general but not under the authority of the province, to be located someplace other than Sinsinawa, and with its own “special statutes”, termed a directory.

According to Let Us Set Out, work then got underway to craft this directory and come to an agreement, and again the Council had rather restrictive specifications for what could be included, for instance they stripped out apparently quite a bit of language “of a Christological nature” which the Congregation for Religious ordered added back in before approving the directory. I had to strongly wonder if Sister Francis was the source of this language and if it centered particularly on the Eucharist; she was certainly the theologian of the group, and in fact back in 1968 when she was at the Mound working on her thesis, had been one of the congregation’s two appointed theologians to evaluate and advise when they were drafting the interim constitutions for the experimentation period. An agreement was not reached on the matter of admitting candidates for formation, this was to be reviewed in two years’ time. It never did come to pass that the experimental community was permitted to admit candidates, nor, according to the Sinsinawa archivist, did they have any women asking to enter religious life through them. But this diligently-pursued and valiant effort, this dream that in hindsight appears to have been the last best chance for a healthy renewal from which growth in new members could spring forth within the Dominican Sisters of Sinsinawa, founded on those sisters who still embraced the Catholic Church’s understanding of religious obedience, who embraced Catholic orthodoxy, who embraced living a traditional lifestyle in community, with traditional teaching apostolate, strongly caught my imagination.

They were offered a convent at the Cathedral Parish in Rockford, IL by Bishop Arthur J. O’Neill, who was the brother of a Sinsinawa Dominican. The appeal of this location was particularly that the parish had a perpetual Eucharistic adoration chapel (this was certainly Sister Francis Assisi’s reason for preferring it, and she would remain there years longer than the others), and that it was not far from Boylan High School, where some of them could teach. They called it Our Lady of the Blessed Sacrament Convent. The Holy See approved the group’s directory in January of 1982, and Sisters Julius Loosbrock, Clementia Kelly, and Gemella McLoughlin moved in the next month. “Sister Francis Assisi Loughery joined them on May 28 after completing her contract with the Leonine Commission in Washington, D.C. Mother Benedicta Larkin became the fifth member on May 31. On that same day, the community held its elections, naming Sister Julius as prioress and Sister Francis Assisi as sub-prioress.”

My information about how all this turned out is perhaps too limited to conclude anything at all from it. The fact that it did not strongly succeed was not necessarily because of opposition from congregation leadership. I understand that the first sisters, perhaps motivated by a sense that they were re-founding their congregation, had some rather rigid expectations, for instance, allegedly it was a very severe sin not to clean out the dryer lint. A sister who had not lived at the Rockford convent but had some knowledge of it, thought that there may have been some very traditional expectations of the sort of keeping silence much of the time–though she was not certain the specific rules of the Rockford house. And the arrival of Sister Francis Assisi and Mother Benedicta, intelligent, humble women, which should have been cause for greater joy, somehow disturbed the serenity of the house; for whatever reason Mother Benedicta moved back to the Mound the next year. Sister Virgilius Thackrey joined in the summer of 1982, and in fall of 1983 Sister John Eudes Courtney (who’d been at Christendom College) and Sister Marciana Mayer.

Sister Mary Julius Loosbrock, who had spearheaded and led the initiative, transferred in 1986 to the well established CMSWR order, the Dominican Sisters of Saint Cecilia in Nashville, TN. She served as registrar at the order’s orthodox Catholic Aquinas College in Nashville, before passing away following an illness in 2008. The Nashville Dominican sister who contacted Sinsinawa to tell them of Sr. Julius’ death “commented on how much Sister Julius loved the Sinsinawa Dominicans.”

Although it is true that Sister Cecilia the prioress general did not like the whole idea and was not really supportive, the most proximate cause of Our Lady of the Blessed Sacrament never fulfilling the great hopes may have had as much to do with being frail and limited humans. God willed that they try. Being humanly successful is not the measure of who is a saint.

Sister Virgilis transferred to the congregation’s retirement housing Saint Dominic Villa in fall of 1983 around the same time Mother Benedicta back to the Mound, and Sister Gemella went to the Mound the following year. Sister Gonsalvo Manderscheid joined in the fall of 1985 and was there only till the next year, Sister Maria Giovanna Loffredo joined in 1986 and she also was there only till the next year, and Sister Rosa Rauth came in 1990 and was there until she and Sister Marciana were the last ones remaining there in 1996. Francis Assisi taught at Boylan and probably continued to until she retied to Trinity Convent in River Forest, Illinois in 1994. Her almost lifelong friend Sister John Eudes had become ill in 1989 and returned to the Mound, where she still lives, as does Sister Rosa Rauth, who can be seen playing a brilliant version of “Happy Birthday” on the piano with another habited sister, in an awesomely cute YouTube video. These last two are the only former members of Our Lady of the Blessed Sacrament Convent still living (as I write this in June of 2013).

Trinity Convent in River Forest IL, where Sister Francis Assisi retired to in 1996, was closed in 2002 due to the associated high school needing the space for other uses. The remaining sisters moved to Divine Providence Convent in the Chicago suburb of Des Plaines, IL, a facility owned by the Sisters of the Holy Family of Nazareth and used jointly by sisters of a few different congregations. “It is a lovely building in a beautiful location near a river and a woods, near a hospital, near a golf course and a cemetery. We are sad to be leaving River Forest, but grateful to God and to our congregation that we can stay together as a community in a convent that will accommodate our needs,” wrote Sister Angela Donovan, the prioress of the house, who had been in the novitiate with Sister Francis Assisi and subsequently become the first principal of Saint Dennis School in Madison. The last Sinsinawa Dominicans moved out of Divine Providence Convent in August, 2007 and the congregation does not seem to have any remaining canonical religious house with a prioress, outside of Sinsinawa, despite still having around 500 sisters as I write this in 2013.

The SinsinOP email discussion list archive begins in 1999, and it was by reading that, that I became aware of, and a very great admirer of, the otherwise rather obscure Sister Francis Assisi Loughery, who at the time the first messages appear (1999) living at Trinity. In my quest to understand how it was that the Sinsinawa Dominicans had gotten from their holy founder Father Samuel Mazzuchelli, to apparently mostly believing in “women priests” as I had experienced in a surreal visit to Sinsinawa Mound to view a film called “Band of Sisters,” had read through great volumes of sisters’ emails full of various dissent and things which caused me real dismay, when I found this one outstandingly good and true sister, Francis Assisi Loughery. Sister Francis was not directly a member of SinsinOP, but on her request Sister Angela Donovan or another sister posted her messages. This below is from the first, in July of 1999. It also made extensive reference to Chapter enactments and the Constitutions, which Sister Francis was calling on the sisters to fulfill.

WHAT DOES THE WORLD NEED FROM DOMINICANS AS WE ENTER THE TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY?

HOLINESS. Consider the incredible influence of Mother Teresa of Calcutta, Blessed Padre Pio, whom our Holy Father recently described as “the Friar who astonished the world,” the brilliant Carmelite mystic, Edith Stein, and so many other saintly religious women and men. Holiness is what draws people to the Lord.

Holiness is essential to mission. Indeed, holiness is mission. This is a recurring theme of Pope John Paul II. Speaking to priests and women/men religious a number of years ago, he made clear: “Your first apostolic duty, [that is, your first mission], is your own sanctification… No movement in religious life has importance unless it be also movement inward to the ‘still center’ of your existence, where Christ is.” […]

As we approach the Third Millennium, I maintain that HOLINESS is what the world needs from Dominicans, because holiness is our mission: our personal mission and our mission to the world.

Her reflection seems to have been stimulated by question #1 of a governance task force survey asking what phrase best describes the Sinsinawa Dominicans’ charism. In another message the following month, she continues reflecting on the survey’s findings.

Some Sisters–150, to be exact– think [our charism] is “preaching and teaching the Gospel”. I was one of these Sisters. We always seemed to identify our charism with our apostolate. This is a biblical concept (ICor. 12:4 ff.), “charisma” is a gift from God for the service of the community (AN ANALYSIS OF THE GREEK NEW TESTAMENT II, Zerwick & Grosvenor, p. 522.) There are 347 Sisters, however, who believe our charism is the essentials of our life: “ministry, prayer, study and community[….]”

Then Sister Francis Assisi does something so characteristic of her, and so rare for anyone else on SinsinOP: she quotes a church document!

In the third chapter of DIRECTIVES FOR MUTUAL RELATIONS BETWEEN BISHOPS AND RELIGIOUS IN THE CHURCH, (a S.C.R.S..I. [Sacred Congregation for Religious] document), there is a section entitled “The Distinctive Character of Every Institute.” It reads, in part:

“The ‘charism of the Founders’ appears as ‘an experience of the Spirit’ transmitted to the followers to be lived by them, to be preserved, deepened and constantly developed in harmony with the Body of Christ continually in a process of growth. “It is for this reason that the distinctive character of the various religious Institutes is preserved and fostered by the Church.” (LG 44; CD 33, 35)

This ‘distinctive character’ also involves a particular style of sanctification and apostolate which creates a definite tradition so that its objective elements can be easily recognized.”

She suggests this could mean their charism is both of sanctification or holiness, and of the apostolate, preaching and teaching the Gospel. And this is a fine answer. The founder’s own answer, though, shows Sister Francis Assisi even more brilliantly as someone who lived up to the Sinsinawa Domininican vocation. He affirms in his commentary on the sisters’ Rule that

it is the special vocation of the Third Order of St. Dominic to oppose religious error in all its forms; and in this country it has as great a work, and perhaps a greater one than the times of its holy founder [ie. St. Dominic], because false doctrines and bad morals surround our Catholic youth on every side. The Sisters, then, in teaching the Catholic doctrine, by words and example, to the children of this country, where they are exposed to lose their faith, do fulfill the main duty of their vocation, and become the true children of their Patriarch [Dominic], and worthy of the name Order of Preachers.

The next month, September, another posting emphasized the call to holiness as essential to getting vocations, the dearth of which had become an increasing crisis: “Holiness attracts new members; holiness sustains veteran members. For many of us, when we prostrated before the altar on profession day, the choir sang the responsory: AMO CHRISTUM. Our religious life is merely a deepening of that same theme. This is our theme song: AMO CHRISTUM.”

In the reflection Angela Donovan, who was close to her during the Trinity years, gave at Sister Francis Assisi’s wake service, she said:

Praying the daily office, Francis prayed aloud to the saints for all who are in need for our prayers. She loved our community fiercely and attended all Chapters, challenging us to be what we professed–of one heart and mind.

In a February, 2000 General Chapter report, we get a glimpse of Sister Francis Assisi’s witty personality and the affection between her and her Sisters. It sounds like she may have been framing in scholarly terms, the shared memory of when convent life and school life was so very regimented by bells marking off time periods: “On Friday evening we were royally entertained by Sr. Francis Assisi on the ‘Hermaneuics of the bell, the methodology of the bell, and the praxis of the bell.'” (The Sinsinawa Dominican Sisters’ 1904 book Golden Bells in Convent Towers, the Jubilee Story of Father Samuel and Saint Clara waxed poetic about obedience to bells at Sinsinawa Mound: “For the bells have no subjects so loyal and so prompt to obey as the true religious, to whom the community bell is ‘the voice of God.'”) A sister who lived with Sister Francis Assisi at Trinity Convent (and who, perhaps I should say, did not know of this project) didn’t share all her sensibilities, but described her warmly as a holy person with a joyful spirit, who loved parties.

On May 23, 2000, she sent a message (via Sister Angela again) that I recognize the necessity of, because when I’d been at Sinsinawa Mound in January both I and the friend I was with were told by sisters regarding the matter of “women’s ordination” that one must follow one’s conscience–but when I said that I believe what Vatican II says, Catholics are obliged to form their conscience in keeping with Catholic teaching, the sister I was speaking with was surprised as if she hadn’t heard that, and didn’t seem to know what to say. Another sister seemed to have a “you have your truth and I have mine” attitude as if she did not believe in objective Truth. The sisters’ misconceptions about conscience have been actively formed in that way, for instance late last year the prioress urged the congregation to view a video (summarized in my article on Truth and Conscience), which was made by Dominican sisters in response to the LCWR doctrinal assessment, arguing extensively that their dissent from settled Catholic teaching can be morally right and “licit.” In fact, what Sister Francis Assisi tried to tell them in 2000 is the truth. Incidentally, as far as I can tell she seems to have been the only sister ever to directly cite the Catechism of the Catholic Church as a source of information, in the 13+ year history of SinsinOP.

This message is from S. Francis Assissi Loughery.

What a sad contrast between Archbishop designate Edward Egan’s pledge of loyalty and obedience to the Holy Father, and the oxymoronic phrase, ‘loyal opposition’ to the Church, adopted by Frances Kissling, president of Catholics for a Free Choice.

A number of years ago the Canadian Conference of Catholic Bishops issued their Statement on the Formation of Conscience. It read in part:

“For a Catholic, ‘to follow one’s conscience’ is not…simply to act as his unguided reason dictates. ‘To follow one’s conscience’ and to remain a Catholic, one must take into account first and foremost the teaching of the Magisterium. When doubt arises due to a conflict of “my” views and those of the Magisterium the presumption of truth lies on the part of the Magisterium.”

Lumen Gentium #25 explains why:

“In matters of faith and morals, the bishops speak in the name of Christ, and the faithful are to accept their teaching and adhere to it with a religious assent of soul. This religious submission of will and of mind must be shown in a special way to the authentic teaching authority of the Roman Pontiff, even when he is not speaking ex cathedra.”

More recently we have the wisdom of the Catholic Catechism which our Holy Father has declared “to be a sure norm for teaching the faith.” (See The Teaching Office of the Church, pp. 23-25.)

If we are called to proclaim the Gospel through the ministry of preachingand teaching, then the hallmark of our authenticity is our fidelity to the official teaching authority of the Church.

S. Francis Assissi Loughery, O.P.

The following day, the 24th, there was a follow-up message:

Yesterday when I sent an e-mail relevant to Frances Kissling, President of Catholics for a Free Choice, and her response to the Bishops’ statement on her organization, I regretted that I did not have a copy of the Bishops’ statement at hand. However, now I do. Her remarks should be evaluated in this context.

A Statement from the National Conference of Catholic Bishops: “For a number of years, a group calling itself Catholics for a Free Choice (CFFC) has been publicly supporting abortion while claiming it speaks as an authentic Catholic voice. That claim is false. In fact, the group’s activity is directed to rejection and distortion of Catholic teaching about the respect and protection due to defenseless unborn human life.

“On a number of occasions the National Conference of Catholic

Bishops (NCCB) has stated publicly that CFFC is not a Catholic organization, does not speak for the Catholic Church, and in fact promotes positions contrary to the teaching of the Church as articulated by the Holy See and the NCCB.“CFFC is, practically speaking, an arm of the abortion lobby in the United States and throughout the world. It is an advocacy group dedicated to supporting abortion. It is funded by a number of powerful and wealthy private foundations, mostly American, to promote abortion as a method of population control. This position is contrary to existing United Nations policy and the laws and policies of most nations of the world.

“In its latest campaign, CFFC has undertaken a concentrated public relations effort to end the official presence and silence the moral voice of the Holy See at the United Nations as a permanent observer. The public relations effort has ridiculed the Holy See in language reminiscent of other episodes of anti-Catholic bigotry that the Catholic Church has endured in the past.

“As the Catholic Bishops of the United States have stated for many years, the use of the name of Catholic as a platform for supporting the taking of innocent human life and ridiculing the Church is offensive not only to Catholics, but to all who expect honesty and forthrightness in public discourse. We state once again with the strongest emphasis:

“Because of its opposition to the human rights of some of the most defenseless members of the human race, and because its purpose and activities deliberately contradict essential teachings of the Catholic faith….Catholics for a Free Choice merits no recognition or support as a Catholic organization.”

S. Francis Assissi Loughery, O.P.

2000 was the year of the golden jubilee for the sisters who had entered in 1950, including Sisters Francis Assisi, Angela Donovan, and Kaye Ashe. From Trinity Convent, Sisters Angela and Francis sent a warm joint thank-you message to SinsinOP, in which they also promised to have a Mass said for everyone who had worked on the Jubilee celebration, a list which did not fail to include the maintenance and grounds people.

What can we say for all your prayers and your presence at the Mound and around the world at the time of our celebration of Jubilee? Loving service that nourished our bodies, minds, and spirits surrounded us and our guests every moment of the week-end. Greetings too numerous to mention (our Tulip Bags are over-flowing) brought us joy and remembrances of Fifty Years of relationship with God and with this wonderful Sinsinawa congregation.

In July, Sister Francis Assisi again exercised diligence in informing the sisters on morally serious matters, posting in 6 separate parts the entirety of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith’s “Notification Regarding Sister Gramick and Fr. Nugent“, the notorious founders of “New Ways Ministries” outreach to homosexuals, who refused to state personal agreement with Catholic teaching on the sinfulness of homosexual acts (Sr Gramick to this day is an activist against the natural moral law on this matter). Other SinsinOP members were obviously supportive of Gramick.

Former prioress Kaye Ashe, who had made final vows in the same year as Sister Francis Assisi and been in Fribourg in doctoral studies at the same time, one of the most radical Sisters in the community, responded with a three part posting of an article titled “Irreconcilable Differences?” by Sister Brenda Peddigrew, RSM, which generalized that sisters “are unequivocal in their support for Jeannine’s action, and recognize its larger implications,” while on the other hand “groups express sadness and personal support for Jeannine, but equally emphasize the need to keep open dialogue with the Church, staying away from condemnation of the Church’s action.” The author seems angry at this restraint on the part of the groups, and speaks of growing tensions between religious women and “the institutional church.” She insists that “It is a documented pattern in the history of patriarchy that whenever more feminine values have risen to public recognition, thereby threatening to transform closed systems, a fearful hierarchical authority has stepped up its restriction of thought and speech. This, I believe is one way of seeing what is happening now. We are seeing a woman refusing to be silent about an action oppressive to her conscience, a woman refusing to collude with a structure whose main purpose is to control, not to set free.” Pettigrew claims (entirely wrongly, and neglecting to explain that Vatican II emphasizes that Catholics are gravely obliged to form their conscience in keeping with Catholic teaching) that the Church’s action is opposed to Vatican II, and “Being silent about it perpetuates the mental and spiritual imprisonment that women of conscience can suffer within the Roman Catholic Church when their thinking disagrees with its teaching. It negates the prophetic role that is of the essence of religious life, at the heart of our purpose.” There is no counter-response from Sister Francis Assisi, though we do not know whether because of the latter not being a member of SinsinOP, or because (as indeed is so) she has adequately fulfilled her moral obligation to tell them.

The next February, one of the (still) youngest Sinsinawa Dominicans, Sister Laurie Brink, who later became semi-famous when her speech to the LCWR citing the concerning fact that some sisters are moving beyond the Church and even beyond Jesus was quoted in the LCWR doctrinal assessment, gives props to Sister Francis Assisi’s warm exhortations on holiness: “I agree with Sr. Frances Assisi. When echoing the Pontiff, she urges us to respond to the call to holiness. It is the holy which called us here. It is the holy which sustains us. It is the holy in our lives, congregation, church and world we are called to proclaim.”

In April of 2001 Sister Francis Assisi underwent some surgery, I believe after a broken bone, and was touched by the warm support of the community–one of their virtues certainly seems to be that they are there for the sick with cards and letters.

Her health difficulties did not prevent her from caring enough to post in July , soon after Kaye Ashe posted, supporting with “joy” the dissent position, a very informative and very orthodox explanation of why women cannot be ordained as priests, quoting from the document Ordinatio Sacerdotalis, detailing the Vatican’s recent (1991) intervention to try to prohibit Sister Joan Chittister from attending the Women’s Ordination Worldwide Conference, which was thwarted by Sister Joan’s superior Sister Christine Vladimiroff, OSB refusing to enforce the prohibition, which Sister Francis Assisi emphasized was a serious dereliction of the appropriate exercise of the authority of a religious superior:

Dialogue between superior and member are very important, but Vatican II makes a clarification: “…a superior should listen wilingly to /her/ subjects and encourage them to make a personal contribution to the welfare of the community and of the Church. Not to be weakened, however, is the superior’s authority to decide what must be done and to require the doing of it.” (Perfectae Caritatis, #l4) All religious superiors are bound to exercise this authority: to decide what must be done and to require the doing of it.

What a marvelous inspiration it would have been for Sister Christine’s community —and all of us–to have heard her say: “Roma locuta, causa finita.”

The Sinsinawa community had experienced a somewhat similar crisis in which the Vatican had demanded recantation from sisters, including Sinsinawa Dominican Donna Quinn, who had signed a letter calling for the Church to be open to Catholics supporting abortion rights. The congregation had covered for Donna, who did not actually change her thinking or mend her ways.

A reply by a sister who was apparently fine with the Erie Benedictines’ dissent said:

Dear Sr. Francis Assisi,

I highly respect your opinion and your right to express it, but I must ask you not to speak for “all of us”; I was greatly inspired by Sr. Christina’s statement as it stands and would have been greatly dismayed by “Roma locuta, etc.” What a courageous woman she is.

But was she courageous? She was guaranteed the support of most of the press, especially the dissent organ National Catholic Reporter (the favorite publication of Sinsinawa), and 127 out of 128 members of the Erie Benedictines signed a letter supporting Sister Joan’s right to engage in “women’s ordination” activities, while Sister Francis Assisi was virtually alone in speaking out within her religious community, against heterodoxy and dissent on this matter.

When I myself was at Sinsinawa earlier this year, and stood up in the large auditorium full of sisters and was given a mic to ask a question to the filmmaker of “Band of Sisters”, I questioned the inclusion of “women’s ordination” dissent figure Theresa Kane and same-sex dissent figure Jeannine Gramick in the film and pointed out that “of course, the Church has no authority whatsoever to confer priestly ordination on women” (this is from Ordinatio Sacerdotalis). The Call-to-Action linked filmmaker responded that “It takes a lot of of courage to ask that question” and that Theresa Kane and Jeannine Gramick speak to a lot of people. After the film, I tried in vain to find a single Sinsinawa Dominican who believed as the Church does that “women’s ordination” is not possible. I believe Sister Francis Assisi was a truly courageous woman, and best of all it was courage with charity.

Sister Francis Assisi’s brother Francis, passed away in Chicago in mid May, just as the sisters were preparing to move out of Trinity Convent and to Divine Providence Convent in Des Plaines.

This is a message from Sister Francis Assisi. Dear Sisters, Thank you so much for your beautiful expressions of sympathy on the occasion of my brother’s death. Originally I had planned to write each of you a personal note of appreciation, but as the days of our departure for Des Plaines draw near, packing unfortunately takes precedence. Know, however, how grateful my Family and I are for your prayers and your compassion. At the Mass of Christian Burial, I shared an excerpt from a sympathy card we received the previous day. It read: Grief diminishes as memories nourish the heart. Your prayers and solicitude have already diminished our grief, and, in time, it will vanish; but the memory of your Dominican kindness will nourish our hearts forever. Gratefully in the Lord of Life, Sister Francis Assisi, O.P.

There was another, more unexpected loss in July, a 34 year old cousin who died suddenly in Florida. The sisters responded, as is characteristic of them, with many prayers which were very touching to the grieving family. Sister Francis said, “What a blessing this coast-to-coast prayer line is! Thank you for using it.”

Sister Francis Assisi Loughery in old age, from her official obituary sent by the Sinsinawa Mound archivist. Probably published in Sinsinawa’s newsletter Spectrum. Not only did she not quit the habit, she never switched to the modified veil.

By early November the 81 year old sister was seriously ill, I do not know in what way, and under tender care at Sinsinawa Mound. Prayers were requested for her on SinsinOP on November 7th and by another sister on the 8th. Her end was surrounded by the love of old friends, including Sister John Eudes, who watched by her side in the last days. “Dear Sisters, Sister Francis Assisi Loughery was called to eternal life by the Lord and Giver of life on the evening of November 10, 2003, in the 53rd year of her profession. Srs. Joris and Patty, two of her postulants, were with her when she died. How lovely is your dwelling place, O Lord, God of Hosts!” Quam delicta tabernacula tua, Domine virtutum–Father Mazzuchelli’s favorite hymn, from psalm 83, which was also for the sisters the joyful anthem of the consecration to God.

After Sister Francis Assisi’s passing, a sister of a far less orthodox stripe wrote on SinsinOP that she found herself distracted by thoughts of her, particularly a strikingly warm memory from an Eastern Province Chapter meeting:

It was the last day and I was at the same table. The topic of Eucharist was being discussed. Sister Francis had a different theological perspective than all the rest of us. Yet there was a real sense of unity at that table. We all respected her and she in her own gracious way accepted and respected us. Her wonderful sense of HUMOR always came forth. Yes, she will be missed for her graciousness, her faithfulness, her kindness and her wonderful sense of humor. May she enjoy forever God’s loving embrace.

As her body arrived to her wake service, Sister Mary Ellen Winston described Sister Francis Assisi Loughery as

a very gifted woman, very intelligent and yet humble in speaking about her achievements. She was diligent in her search for truth and not afraid to speak her truth. Francis grappled with hard questions. She had about her a presence, a peacefulness. Her wit and dry sense of humor brought us to another awareness of her many gifts.

Sister Francis Assisi’s funeral was celebrated by Bishop Arthur J. O’Neill, who had invited the group of which she was a part to live at the convent of his Cathedral Parish in Rockford, and who became a friend. Her surviving biological sister, Dorothy Walsh, who has now passed away in 2013, was there too. The homily was given by Father Jack Risley, O.P., one of Sinsinawa’s resident chaplains. Sister Francis Assisi’s theological work on the Eucharist, he said, “was something she loved, something she had a passion for, her delight in pursuing the truth, her belief that any part of God’s wisdom that she could obtain would be an ‘incalcuable wealth.’ It would be to know Jesus Christ, and thus be ‘filled with the fullness of God.” She is buried in the congregation’s cemetery on the western slope of the Mound.

—

It should be better known that there was a valiant, if imperfect and unsuccessful plan to carve out space within the Sinsinawa Dominicans for a more traditional way of life and a re-commitment to Catholic schools, and for the reception of sister candidates with more traditional expectations of religious life, which was nurtured by a small group of sisters who had the support of the Holy See. Every religious who stands up within a community environment of hostility toward Catholic doctrine and morals, and communicates the truth in charity, is to be commended.

The members of the Father Mazzuchelli Society are very deeply impressed by the holy example of Sister Francis Assisi Louhgery, O.P., her love for Jesus in the Eucharist, and the exemplary way in which she lived out her congregation’s charism as articulated by the founder Father Samuel Mazzuchelli.